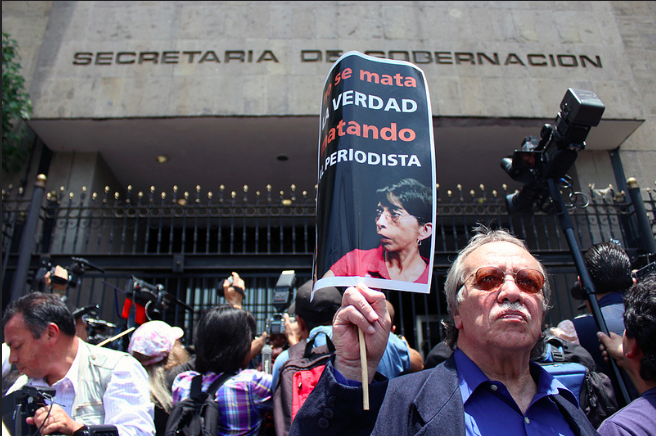

Journalists protest in front of a Veracruz government building. Veracruz continues to be one of the most dangerous regions to practice journalism because of the number of murders that have occurred there. Photo taken from the Flickr account of CimacNoticias Agency under Creative Commons license.

This post by Mariana Muñoz was originally published originally on the blog Journalism in the Americas and is republished here with permission.

In the last decade, Mexico has become one of the most dangerous countries of the world for journalists, largely due to the so-called War on Drugs in the northern region that borders the United States.

Press freedom advocacy organizations, however, noticed a change in the geography of attacks against journalists, which are increasingly becoming more common in Mexico's southern states. They also noticed that the suspects behind the attacks are not members of drug cartels, but public officials and police officers.

Violence shifts from north to south

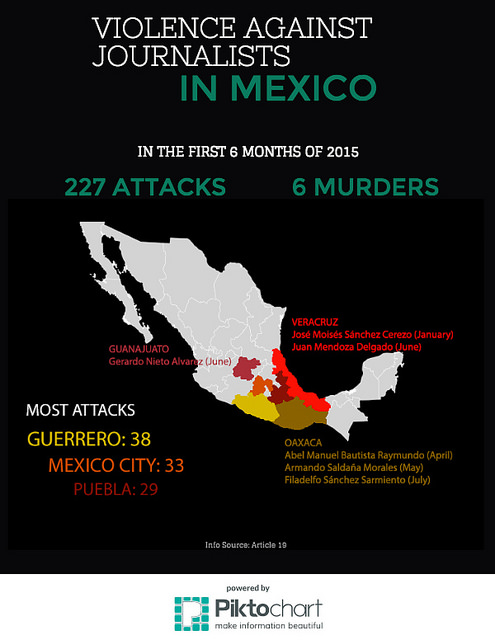

This year, so far, there have been six cases of journalists being murdered – all were killed in Mexico's south. In one week this July, three journalists were killed in Oaxaca, Veracruz and Guanajuato – all southern states.

Statistics from Periodistas en Riesgo, a site that tracks and documents attacks against journalists in Mexico, seems to confirm this trend.

Javier Garza Ramos, an International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) Knight International Journalism Fellow who oversees Periodistas en Riesgo, recently wrote an article for El País where he explores the shift of violence from the north to the south.

Garza explains that the shift occurred because, in general, violence in the north decreased (with the exception of Tamaulipas) and shifted attention to the increasing incidents in the central and southern states.

In an interview with the Knight Center, Garza stated that there is a misconception on who is doing the most harm, however.

Public officials and police officers are now the main aggressors

According to Garza, attention has been largely focused on attacks against journalists by cartel members because they have been the most dramatic in the manner in which they attack. Consequently, cartel members are seen as the main aggressors toward journalists.

Garza argues that this is not true.

“They are the ones who attack more violently, but in quantitative terms, they are not the ones who attack the most,” he said.

According to Garza, public officials and police officers are responsible for most of the attacks toward journalists. The manner and intensity of attacks vary, ranging from threats and intimidation to kidnapping, beatings and homicides.

Freedom of expression in Mexico has taken a hit in recent years. Journalists in this country face threats from public officials and members of organized crime, leading to injuries and in some cases, death.

“Organized crime violence has started to decrease in northern regions like Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, compared to 2010 and 2011. Tamaulipas is the only exception,” he said.

A recent event recorded by La Crónica appears to demonstrate the trend of public officials threatening or attacking journalists.

Daniel Blancas, reporter for La Cronica, was sent to the municipality of Almoloya de Juarez in the state of Mexico to investigate the escape from prison of Mexico’s biggest drug lord, Joaquín Guzmán Loera, also known as El Chapo. His job was to interview Calixto Estrada Castillo, the last owner of the house that served as the end point for Guzmán Loera's escape tunnel.

After being questioned and prohibited from entering the premises, Blancas says he received a threat: “Cemeteries are full of journalists like you!”

According to Huellas de Mexico, the threat was made by Jorge Peña, an official with the Office of the Attorney General in Zinacantepec.

Veracruz: “hell for journalists”

According to the first bi-annual report of 2015 by Article 19 titled, “Más violencia, más silencio” (“More violence, more silence”), 227 attacks against the press were recorded in the first six months of 2015. This is substantially higher than the average during Felipe Calderón’s administration from 2006 to 2012, which was about 182 per year, the report added.

The report also discussed the six murders of journalists that have occurred since January 2015, all in the southern part of the country.

Three of the six murders have occurred in Veracruz, located in the southeastern portion of the country on the coastline of the Gulf of Mexico.

Even though the state of Guerrero has the highest number of overall attacks toward journalists (38), Veracruz continues to be one of the most dangerous regions to practice journalism because of the number of murders that have occurred there, according to Animal Politico.

In a BBC Mundo article, the state is referred to as “hell for journalists.”

Eighteen journalists have been murdered there since 2000 and 12 of these murders (14, according to other sources) have been recorded under the administration of current governor Javier Duarte, according to Article 19.

A documentary titled, “Death in Veracruz” produced by the all-digital channel AJ+, explores the manner in which the lives of journalists in Veracruz have changed, working under threat in recent years.

In 2011, the municipal police in Veracruz were dismantled due to alleged corruption and the fact that the army began to carry out their duties.

Self-defense groups, upset with the ineffectiveness of police, formed in the state.

Félix Márquez, a photojournalist in Veracruz, documented the groups.

“The authorities don’t want to recognize that these groups exist,” he said. “I don’t know why they don’t like to talk about the self-defense groups. However, our job is to document them and prove they exist.”

Márquez said he was threatened over his photos of the self-defense groups.

“The Secretary of Public Security made a statement saying that I should be in prison,” he said in the documentary.

“Death in Veracruz” also explores the case of José Moisés Sánchez Cerezo, a journalist who was killed in Veracruz on January 2.

Sánchez founded the daily La Unión in the municipality of Medellín de Bravo in Veracruz to inform the community about things that were not reported by other news outlets.

Often reporting on police corruption, Sánchez was intimidated by public officials, and, in one instance, received word that the mayor was planning to scare him, according to the documentary.

Sánchez was abducted from his home on January 2; his lifeless body was found in Veracruz in the early hours of January 24. Many believe that the mayor, Omar Cruz, ordered his kidnapping and murder.

Jorge Sánchez, son of Moisés, continues to seek justice for the death of his father.

“There are many irregularities in this investigation,” he said in the documentary. “These are the same anomalies that exist in all the investigations of journalists’ murders.”

After the murder, police officers were assigned to monitor the Sanchez’s home—a method of protection for the family. A barbed wire fence was placed around the home.

“One would think that the other people are the ones who should be locked away, not us,” Jorge Sánchez said in the documentary. “But this is how things work here—the criminals roam free and we are the ones who have to be locked in.”

Impunity is a problem in Mexico where crimes against journalists are rarely punished. The country ranks seventh in the Committee to Protect Journalist’s 2014 Global Impunity Index. Additionally, critics have pointed to serious problems with the federal protection mechanism for journalists who are in danger.

5 comments