A year has passed since martial law was declared in Thailand by the army. Last month, martial law was revoked but a new law gave the army ‘unlimited’ powers to rule the country.

This article is from Prachatai, an independent news site in Thailand, and is republished on Global Voices as part of a content-sharing agreement.

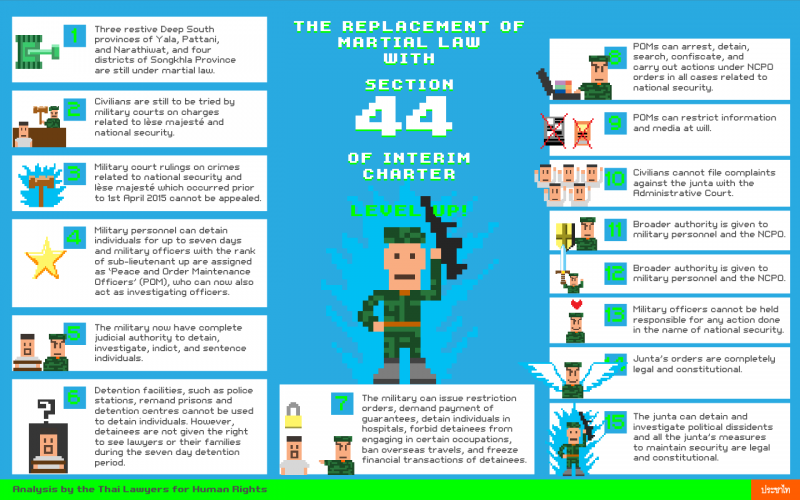

Martial law, which had been in force since May 2014, was finally revoked in Thailand on 20 March 2015. However, instead of returning Thailand to civilian rule as it had promised, the Thai junta replaced martial law with its new protocol, Section 44 of the Interim Charter, which significantly broadens its authority while still retaining the power to crush political dissent with arrests and detentions.

According to Brad Adams, the Asia Director of Human Rights Watch, invoking Section 44 of the Interim Charter provision gives Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, the junta leader and Prime Minister, unlimited power without safeguards on human rights:

General Prayut’s activation of Section 44 of the Constitution will mark Thailand’s deepening descent into dictatorship. Thailand’s friends abroad should not be fooled by this obvious sleight of hand by the junta leader to replace martial law with a constitutional provision that effectively provides unlimited and unaccountable powers.

The following are 15 facts about the sweeping powers the junta has acquired through the imposition of Section 44.

1. Areas under the martial law prior to the May 2014 coup d’état, which cover four districts of the southern province of Songkhla and three provinces of the restive Deep South, Yala, Pattani, and Narathiwat, are still under martial law.

2. Civilians are still subjected to trial by military courts in cases related to national security, such as possessing or carrying unauthorised or illegal weapons in public and instigating rebellion, and those constituting offences under Section 112 of the Criminal Code, known as the lèse majesté law, in accordance to the junta’s National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) Announcements Nos. 37/2014, 38/2014, and 50/2014.

3. Defendants can appeal verdicts handed down by a military court. However, cases under the jurisdiction of military courts which took place between 25 May 2014 and 31 March 2015 cannot be appealed under Section 61 of the 1955 Military Court Act.

4. Under Section 15 of the 1914 Martial Law Act, military personnel can detain individuals for up to seven days, after which suspects are to be sent to the police for investigation. However, NCPO Order 3/2015 under Section 44 assigns ‘Peace and Order Maintenance Officers’ (POM), which are defined as military personnel with the rank of sub-lieutenant up, to act as investigating officers for suspects charged with offences related to national security.

5. Section 44 gives military personnel complete judicial power over detaining, investigating, indicting, and judging in military tribunals, cases related to national security in accordance to the junta’s NCPO Announcements Nos. 37/2014, 38/2014, and 50/2014.

6. POMs can detain individuals for up to seven days in places which are not detention facilities such as police stations, remand prisons and detention centres, and detainees shall not be treated as suspects of criminal offences. Similar to the practice under martial law, detainees are not alleged criminal offenders. Therefore, they are not granted rights to see their families, relatives, or lawyers.

7. While detaining suspects accused of defying junta orders within the seven day time frame, security officers can 1) issue restriction orders, 2) demand payment of guarantees, 3) detain individuals in hospitals, 4) forbid detainees from engaging in certain occupations, 5) ban overseas travel, and 6) freeze financial transactions of detainees. These conditions are more severe than those under NCPO Announcement No. 40/2014.

8. POMs can arrest, detain, search, confiscate, and carry out actions under NCPO orders in all cases related to national security mentioned in NCPO Announcement No. 37/2014.

9. POMs can issue orders to prohibit the circulation of information and news from any source which might cause fear or distort facts or is intended to have a negative impact on national security and public order.

10. Political gatherings of five people or more are prohibited. However, if persons suspected of political gathering charges voluntarily participate in seven day training under POMs, the suspects can be released with or without conditions, free from liability of criminal charges. This POM-run training is based on Section 21 of the 2008 Internal Security Act (ISA). But unlike training under the ISA, which includes a certain level of judicial oversight, the authority to conduct seven days training under this order lies with the military POMs alone.

11. The actions of authorities under Section 44 are not covered by Thailand’s Administration Act and civilians cannot file complaints with the Administrative Court.

12. Section 44 of the Interim Charter gives authority to the leader of the NCPO alone. However, NCPO Order 3/2015, which replaces martial law with Section 44, delegates these powers to other military personnel and NCPO officers. In other words, it broadens the authority of military officers and the NCPO.

13. POMs and their assistants who act impartially in accordance with the authority bestowed by the junta cannot be held responsible for actions to prevent threats to national security.

14. Section 14 of NCPO Order 3/2015 to impose Section 44 does not prohibit affected parties from claiming compensation from the government in accordance with the Public Officials’ Responsibility and Conduct Act. However, Section 44 of the Interim Charter states that orders or actions under the junta’s directives are completely legal and constitutional.

15. In conclusion, the junta’s NCPO Order No. 3/2015 still gives the junta the authority they had under martial law. However, it adds procedures to handle political dissent based on the Internal Security Act, exempts state officials from their responsibilities under the 2005 Public Administration in a State of Emergency Act, and authorizes them to carry out investigations under the Criminal Procedure Code, all of which becomes constitutional and legal in accordance to Section 44.

17 comments