[All links lead to Portuguese language pages, except when otherwise noted.]

Angola celebrated the 37th anniversary of its independence on November 11, 2012. But, in reality, how independent is the country nowadays? In terms of media and social communication, for instance, the reality is disturbing and, according to specialists, the censorship in Angola is becoming more sophisticated.

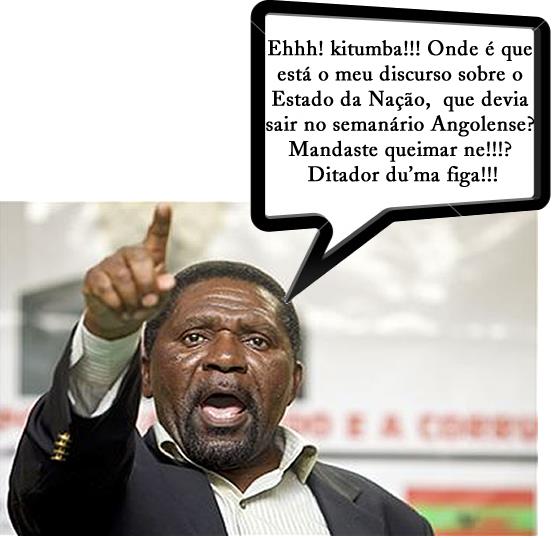

One of the recent episodes of censorship occurred on October 27, 2012, when the newspaper Semanário Angolense was withdrawn from the printing press by the company Media Investe. The reason was the publication of almost an entire speech by the president of the opposition party UNITA [en], Isaías Samakuva, in which he was being highly critical about the state of the nation. Maka Angola published it first:

A empresa proprietária, controlada por altas figuras dos Serviços de Segurança e Informação do Estado (SINSE), retirou os exemplares impressos do jornal para serem queimados. Maka Angola obteve uma cópia digital do jornal censurado, cujas páginas 8, 9 e 10 reproduzem, com tratamento gráfico, o discurso de Samakuva, de 23 de Outubro.

Copy of the cover of the censored Semanário Angolense. The speech given by Samakuva on October 23 is reproduced on pages 8, 9 and 10.

The speech of the leader of Angola's largest opposition party- the full version was made available online by Maka Angola [pdf]- criticised the fact that the Angolan President, José Eduardo dos Santos, has not made the speech on the state of the nation at the opening of third Legislature, as laid down in the Constitution. Instead, the Angolan Head of State asked that copies of his inauguration speech be distributed to the members of parliament on September 26. The move was widely criticised by the opposition and by various sectors of society.

In an interview with DW, the Angolan human rights activist and founder of Maka Angola, Rafael Marques, says that this is “another way to control the information that circulates” in the country:

O presidente da UNITA fez um discurso bastante contundente que teve grande aceitação na sociedade (…). Daí a necessidade de ter que garantir que o discurso de Isaías Samakuva não tenha ampla circulação. Ele está a circular apenas na internet e, como é do conhecimento geral, Luanda e o país sofrem uma grave crise de abastecimento de eletricidade. Logo muito poucas pessoas têm acesso à internet e os jornais são mais lidos, porque um jornal pode ser lido por várias pessoas. Agora também os jornais privados são controlados pelo aparelho de segurança e neste caso houve uma falha dos censores, mas mesmo assim ainda foram a tempo de ir buscar os jornais da impressão diretamente para a queima.

On its website, the Union of Angolan Journalists (SJA) regrets that “incidents” like this are no news in the panorama of “press freedom” in Angola:

Este tipo de atentados começou verificar-se desde a altura, já lá vão mais de dois anos, em que alguns semanários luandenses começaram a ser comprados por empresas sem rosto, tendo neste âmbito mudado de proprietários o “Semanário Angolense”, a “A Capital” e o “Novo Jornal”. Do ponto de vista editorial, “A Capital” foi até agora a publicação que mais foi violentada/censurada pelos seus novos proprietários, por razões claramente políticas e relacionadas com a sua discordância no tocante a determinadas matérias desfavoráveis aos interesses do actual poder político.

The case of the Semanário Angolense generated numerous comments on social networks. On October 29, 2012, Joana Clementina commented on Facebook:

Tanto barulho porquê? O Semanário em questão tem um dono e cabe a ele decidir o que vai para a rua. Se o problema é o discurso do man samas [Isaías Samakuva], a Rádio Despertar pode passar sempre que quiser e diga-se que a Despertar tem maior audiência em relação ao Angolense. No big deal. Ficaria feliz se vocês apontassem soluções para o problema da luz e água. O Semanário Angolense nem está ao alcance do bolso do cidadão comum, uma minoria é que o lê.

Shortly after, Mingiedy Mia Loa responded directly to the comment:

Joana Clementina: independentemente do dono, existe o Conselho Nacional de Comunicação Social e cabe a este órgão regular e fiscalizar a linha editorial dos órgãos de comunicação social, sejam eles privadas ou publicas, e por outra a Constituição de Angola não prevê censuras em matérias jornalísticas no seu capitulo de liberdades de expressão…

On October 31, Maurilio Luiele also wrote on Facebook:

O facto é que a constituição consagra a liberdade de imprensa e ipsis factus proíbe a censura. Se isso não é censura então é o quê? O que está em causa é a violação da Constituição, e pior ainda, a forma sistemática e leviana como se ultraja a Lei em Angola. Sempre me faço a seguinte pergunta: se a lei não é a baliza e livre arbitrio prevalece onde fica o Estado Democrático de Direito? Onde está a PGR para defender a legalidade?

As SJA indicates, quoting the current legislation (Law no. 7/06 from May 15, 2006 [pdf, pt]), the attack on the freedom of press happens when:

[…] aquele que fora dos casos previstos na lei impedir ou perturbar a composição, impressão, distribuição e livre circulação de publicações periódicas, impedir ou perturbar a emissão de programas de radiodifusão e televisão, apreender ou danificar quaisquer materiais necessários ao exercício da actividade jornalística.

“Should the freedom of each individual not be respected?” questions the researcher Eugenio Costa Almeida in an opinion piece on the subject, published in the Angolan weekly Novo Jornal, on November 2:

A ser verdade esta eventual atitude, deram mostras de não respeitar a liberdade de cada um. A liberdade de quem escreveu, a liberdade de quem produziu e, mais grave ainda porque a condiciona, a liberdade de escolha do leitor. Porque os jornais, a comunicação social, só existe porque há leitores, ouvintes e telespectadores que lêem, ouve, ou vêem as notícias e as opiniões emitidas para, posteriormente, terem a liberdade de as apreciar, citar ou questionar e criticar as mesmas e delas tirarem as ilações possíveis.

Episodes like this are proof that the Angolan “lapis azul” (blue pencil- a symbol of censorship) is taking on new dimensions, with propaganda and censorship increasingly restricting press freedom. The Angolan model of censorship is even “more sophisticated than the Chinese”, argues the Angolan analyst Nelson Pestana in an interview with DW:

O modelo de censura chinês é assumido como um dos mecanismos do partido. Em Angola não. O discurso de legitimação passa pela ideia de democracia, pela ideia de pluralismo. Não é um órgão exterior que impede o jornal de circular é o próprio dono do jornal que decide que desta vez não circula. Só que o dono do jornal faz parte do grupo do poder e por isso é evidentemente um mecanismo de censura e de controlo da opinião pública nacional.

“None of the countries of the PALOP [African Countries of Official Portuguese Language] has the means of pressure that Angola has”, criticised the Portuguese journalist Pedro Rosa Mendes in an interview in February this year, shortly after the radio programme he worked with (Este tempo, broadcast on the public radio Antena 1) had been suspended after the broadcast of an opinion piece [en] which criticised the Angolan government:

É óbvio, para toda a gente que não queira ser ingénua, que muita da pressão que Angola pode fazer já funciona por si. É uma espécie de diplomacia paralela e de pressão tácita.

This post was proofread in English by Georgi McCarthy.

3 comments