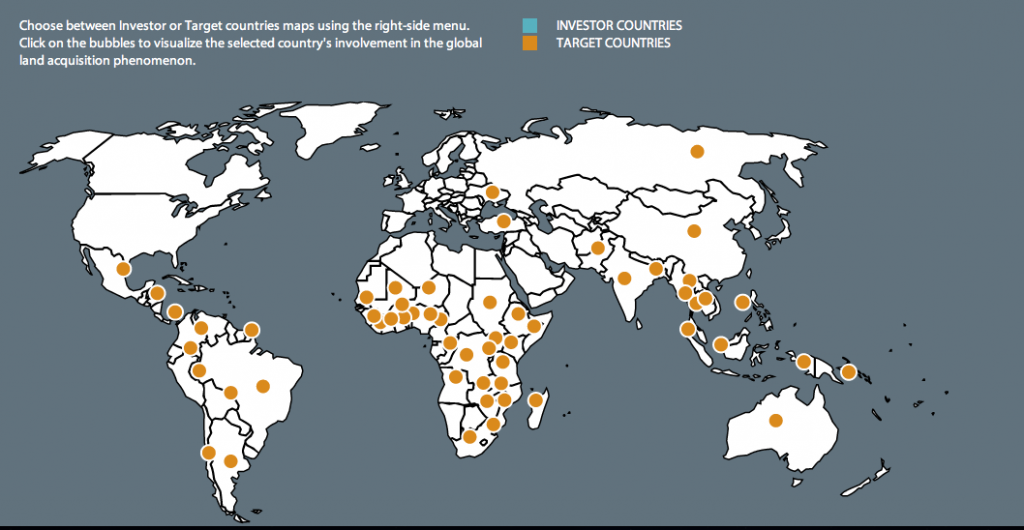

An international coalition of researchers and NGOs have released the world's largest public database of international land deals, reports the Global Development blog of The Guardian's (UK). This marks an important milestone in highlighting a developmental issue that has received little attention in the international news cycle.

The report states that almost 5% of Africa's agricultural land has been bought or leased by investors since 2000, and emphasizes the fact that this is not a new issue, yet points out that the number of such land deals has increased tremendously in the past five years.

Many observers are increasingly worried that these land deals usually take place in the world's poorest countries and that they impact its most vulnerable population, the farmers. The benefits seldom go to the general population, partially because of a lack of transparency in the proceedings of the transactions.

An additional report by Global Witness, entitled Dealing with Disclosure, emphasizes the dire need for transparency in the making of land deals.

World's poorest nations targeted

The Global Witness report lists that 754 land deals have been identified, involving the majority of African countries for about 56.2 million hectares.

The nations targeted are usually some of the poorest in the world. The countries with the most deals in place are Mozambique (92 deals), Ethiopia (83), Tanzania (58) and Madagascar (39). Some of those deals have made headlines because they were conducted to ensure control over food imports, when the targeted regions faced major food crises.

The NGO GRAIN has already explained in detail the gist of their concerns in an extensive report released in 2008:

Today’s food and financial crises have, in tandem, triggered a new global land grab. On the one hand, “food insecure” governments that rely on imports to feed their people are snatching up vast areas of farmland abroad for their own offshore food production. On the other hand, food corporations and private investors, hungry for profits in the midst of the deepening financial crisis, see investment in foreign farmland as an important new source of revenue. As a result, fertile agricultural land is becoming increasingly privatised and concentrated. If left unchecked, this global land grab could spell the end of small-scale farming, and rural livelihoods, in numerous places around the world.

In Malawi, land deals have grown increasingly prevalent to the detriment of the local farmers. A report from Bangula explains the challenges faced by Malawian farmers, Dorothy Dyton and her family:

Like most smallholder farmers in Malawi, they did not have a title deed for the land Dyton was born on, and in 2009 she and about 2,000 other subsistence farmers from the area were informed by their local chief that the land had been sold and they could no longer cultivate there. […] Since that time, said Dyton, “life has been very hard on us.” With a game reserve on one side of the community and the Shire river and Mozambique border on the other, there is no other available land for them to farm and the family now ekes out a living selling firewood they gather from the nearby forest.

Farmers in Madagascar share similar concerns because they do not own the rights to the land they farm and an effective land reform is yet to be implemented. The Malagasy association Terres Malgaches has been at the forefront of land protection for the local population. They report that [fr]:

Les familles malgaches ne possèdent pas de document foncier pour sécuriser leurs terres contre les accaparements de toutes sortes. En effet, depuis la colonisation, l’obtention de titres fonciers auprès de l’un des 33 services des domaines d’un pays de 589 000 km2 nécessite 24 étapes, 6 ans en moyenne et jusqu’à 500 dollars US. (..) . Face aux convoitises et accaparements dont les terres malgaches font l’objet actuellement, seule la possession d’un titre ou d’un certificat foncier, seuls documents juridiques reconnus, permet d’entreprendre des actions en justice en cas de conflit.

The association also reports on the practices of a mining company Sheritt, in Ambatovy, which have created a buzz in the local blogosphere because of environmental concerns for the local population and business malpractices (via MiningWatch Canada):

Sherritt International’s Ambatovy project in eastern Madagascar – costing $5.5 billion to build and scheduled to begin full production this month – will comprise a number of open pit mines (..) it will close in 29 years. There are already many concerns about the mine from the thousands of local people near the facilities. They say that their fields are destroyed ; the water is dirty ; the fish in the river are dead and there have been landslides near their village. During testing of the new plant, there have been at least four separate leaks of sulphur dioxide from the hydro-metallurgical facility which villagers say have killed at least two adults and two babies and sickened at least 50 more people. In January, laid-off construction workers from Ambatovy began a wildcat strike, arguing that the jobs they were promised when construction ended have not materialized. The people in nearby cities like Moramanga say that their daughters are increasingly engaged in prostitution.

Video of a worker's testimony in Ambatovy.

Solutions for the local population?

The plight of Madagascar's farmers’ plight may be slowly changing though. Land reform discussions are in progress, according to this report:

According to a paper presented at the 2011 International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, about 50 agribusiness projects were announced between 2005 and 2010, about 30 of which are still active, covering a total land area of about 150,000 ha. Projects include plantations to produce sugar cane, cassava and jatropha-based biofuel.

To prevent the negative impacts of land grabbing, (The NGO) EFA has set up social models for investors, with funding from the UN Development Programme (UNDP). The goal is to help investors negotiate with the people in the area where they want to implement projects, as a way to prevent future problems.

Joachim Von Braun, formerly of the International Food Policy Insitute (IFPRI), wrote the following regarding land deals:

It is in the long-run interest of investors, host governments, and the local people involved to ensure that these arrangements are properly negotiated, practices are sustainable, and benefits are shared. Because of the transnational nature of such arrangements, no single institutional mechanism will ensure this outcome. Rather, a combination of international law, government policies, and the involvement of civil society, the media, and local communities is needed to minimize the threats and realize the benefits.

The need for transparency in land deals is further emphasized by Megan MacInnes, Senior Land Campaigner at Global Witness:

Far too many people are being kept in the dark about massive land deals that could destroy their homes and livelihoods. That this needs to change is well understood, but how to change it is not. For the first time, this report (Dealing with Disclosure) sets out in detail what tools governments, companies and citizens can harness to remove the shroud of secrecy that surrounds land acquisition. It takes lessons from efforts to improve transparency in other sectors and looks at what is likely to work for land. Companies should have to prove they are doing no harm, rather than communities with little information or power having to prove that a land deal is negatively affecting them.

13 comments

Sadness situation in Africa

It is a pity! Meanwhile the world is looking on