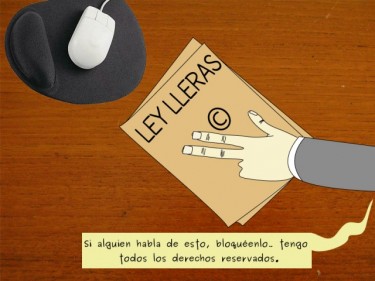

The bill to regulate infractions on authors’ rights on the Internet, known as the “Lleras” Law, has continued generating reactions and debate in the Colombian Internet sphere, as recently covered on Global Voices. This topic has become vital for those who use the Internet, share and post content. The people behind the Red pa todos (Internet for all) initiative, explain [es] the proceedings for the removal and reestablishment of content proposed in the aforementioned bill and conclude by making their doubts about it quite clear:

En este procedimiento es la ISP la que tiene la responsabilidad inicial de decidir sobre el bloqueo o el mantenimiento del acceso y no un juez. El juez aparece al final del procedimiento … Surgen muchas preguntas, por ejemplo ¿Debemos confiar en un procedimiento administrativo de una empresa que tiene comprometida su responsabilidad para decidir algo que evidentemente es de competencia judicial como lo reconoce la propia ley que al final es a él a quien otorga la responsabilidad? ¿Podemos esperar que la ISP estudie y decida sobre otros derechos como libertad de expresión, límites al derecho de autor, competencia desleal, etc? ¿Si en un estado de derecho el garante para su aplicación es el juez (después de siglos de construcción del concepto), porqué debemos aceptar algo diferente cuando se comprometen derechos de todos en la sociedad?

To give similar powers of jurisdiction to the ISP, or Internet Service Providers, under the pretext of content piracy sounds quite risky, even more so when the definition and attributions of an ISP are not even clear in the bill, as the author of Maestroviejo's blog relates [es], and also cites points where he noticed a group of previous work [es] that should have announced the opinion of those interested in a public discussion of the project, something that later was never brought to fruition. Maestroviejo mentions later that possible penalties could reach anywhere between 4 to 8 years in prison and fines of 26.66 to 1000 minimum salaries for the crimes of violating author's rights and related rights (the minimum salary in Colombia is 535.600 pesos, appx. 300 USD) and later emphasizes that the proceedings plan to establish:

Una ley que otorga poderes a Telmex o Telefónica para eliminar contenidos de la red cuando reciba la denuncia del “dueño de los derechos” presuntamente inculcados. Los ISP tendrán que limitarse a informar a quien publicó los contenidos antes de retirarlos o inhabilitar la dirección donde se alojó ese contenido. El proveedor tendrá 72 horas para hacer este trámite. Al presunto infractor que considere injusta la censura de los contenidos de su página le queda entonces, una vez que la telefónica de turno ya ha retirado los contenidos, recurrir a la Justicia.

On Twitter, through the #LeyLleras hashtag and the @contraleylleras account, one can find a lot of information and opinions with respect to this. Initiatives like the Colombia contra la Ley Lleras [es] (Colombia against the Lleras law) blog or HackBo: Hacker Space Bogotá [es], that have implemented a special page on their websites to bring together information, are functioning as hubs for spreading the topic. Although people from Anonymous Colombia [es] are not hackers precisely, this collective has had an active participation against the bill. On April 7, they opened their Twitter account and one of the first tweets [es] was:

Anonymous se une a la lucha contra la #leylleras, enterate de como puedes ayudar en nuestro chat http://irc.lc/anonops/opcolombia.

Later they published a press release [es] and announced [es] their first objective for a DDoS attack, the website [es] for the Colombian Ministry of the Interior and Justice System, which was successfully carried out [es] on April 12. In prior days, they continued the attacks [es] on other government websites such as that of the Senate and the online Government [es], as well as the Presidency of the Republic. At the time of writing this post they find themselves preparing the Paper Storm Operation of Colombia (Operación Tormenta de Papel Colombia) [es] for April 29.

In a similar manner, various pages [es] have been created on Facebook social network to bring widespread coverage of the aforementioned law, the most popular of which [es] has 6757 fans at the time this post was written. Nevertheless, it is curious that in its description it states: “it is worth clarifying that this page does NOT support the subjects that call themselves ‘Anonymous'; for me it is NOT necessary to attack pages. I believe that by getting a dialogue going, as Minister Germán Vargas says, things will fix themselves. As such, this May 4th, a public dialogue was opened.” This other Facebook page has 5724 fans at the moment.

On YouTube one can find a good number of videos [es] about this topic as well. The one that follows, for example, I recorded over the course of one of the Labsurlab [es] sessions in Medellín on April 11. In it, I talk about the activism against the Lleras Law with Elkin Botero [es], who describes himself on Twitter as “Web Developer, Expert on ITCs and Free Software, Musician and lover of life. Member of the Colombian Piracy Party. Without Presumption of Innocence: IAmAPirate”:

Later, at the same event, I was able to chat with Isaac Hacksimov [es], a face visible with what is defined as “a collective identity, the assembly of bodies and machines of the HamLab hacktivist laboratory, a narration of many voices and a single name,” who gave us an interesting and ample vision of things related to the intents to regulate the use of content on the Internet from his experience in Spain:

The next day, I was able to briefly ask journalist Natalia Estefanía Botero [es], in charge of the technology section for newspaper El Colombiano [es], about her impressions regarding this topic:

Finally, the following articles are additional reading material for those interested in researching the topic more thoroughly: “The pros and cons of the Lleras law” [es] and “Lleras law on the table” [es] from Semana.com, the article “¿Copyright or authors with rights?” [es] from Lapizlázuli Periódico and the blog post “11 controversial aspects of the Lleras law” [es] by journalist Camilo A. García.

Similarly, the articles on the law commented on [es] one by one in the aforementioned site Red pa Todos. Additionally, the official blog: Derechodeautor's weblog [es] of the Special Administrative Unit of the National Direction of Author's Rights, with many interesting comments from users.

¿En qué terminará este asunto? Presenciamos un evidente reto de la comunidad virtual colombiana, pues en este país, hasta ahora, Facebook, Twitter y los blogs son redes ‘asociales’ que parecen unir a las personas, pero a sus computadores. Es hora de demostrar que el activismo y la participación virtuales pueden ir más allá de hacer clic en el botón de “Me gusta”.

-Sian Sinnott and Marianna Breytman collaborated in transcribing, translating and subtitling the videos in this post

2 comments