[All links lead to Portuguese language pages except when otherwise noted.]

On 7 April 2011, twelve adolescents at the Tasso da Silveira City School in Realengo [en] in the west of Rio were shot dead. The culprit was ex-pupil, Wellington Menezes de Oliveira, 23, who then turned the gun on himself.

The tragedy stirred up strong feelings of ‘indignation, disgust and consternation’ throughout Brazil, and the blogosphere was immediately filled with expressions of regret and demonstrations of revolt towards the killer.

Detective Chief Inspector Marcus Moura, in a posting on Facebook, showed his disgust and foresaw that the debate which followed the school massacre would prompt deep-rooted questions about Brazilian society:

(…) uma tristeza profunda, uma sensação de total impotência por saber que, nesse tempos estranhos que vivemos, é muito difícil evitar que a sociedade continue a gerar seus monstros. Impotência por fazer parte de um mundo que abriga esse tipo de distorção, essas manifestações exacerbadas não de ódio, mas de infelicidade.

A past of being misunderstood

The growing speculation about the killer’s profile, in both the blogosphere and traditional media, raised various hypotheses about Wellington’s motivation for committing the crime.

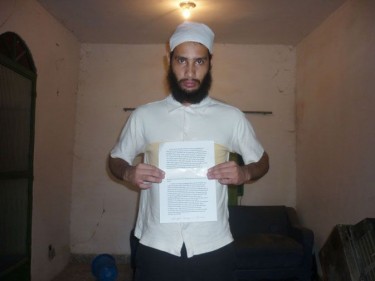

Rumours ran wild that he might be Muslim because of his ‘special Islamic dress’, and other stereotypes were cited.

In the suicide note that Wellington left, together with a fundamentalist speech, he referred to the ‘pure ones’ and the ‘faithful ones’, generating further discussion. The cinema critic and blogger Inacio Araujo in his blog:

Ele faz uma salada de Corão, Bíblia, retórica dos programas evangélicos da TV ou manifestos da Al Qaeda.

When videos from Wellington’s computer began to be made public, it was clear that the various references to the ‘faithful’ and ‘unfaithful’ showed the burden he had carried since childhood, and not any kind of religious leaning. This was a href=”http://jorgewerthein.blogspot.com/2011/04/tragedia-de-realengo-bullying-e-assunto.html”>put forward by the journalists Rodrigo Rotzsch and Diana Brito. They go on:

“Fiéis” ou “irmãos” são os que, como afirma Wellington, sofrem bullying. “Infiéis” e “fornicadores” são os que praticam o bullying ou compactuam com a prática.

In one of his final videos, Wellington, denying responsibility for the deaths which would take place ‘even though [his] fingers [might have been] responsible for pulling the trigger’ put himself up as a spokesperson for all those who had been victims of bullying [en]. This had become an increasingly common kind of physical and moral violence, which not only happens in schools but also in adult life:

Eu ainda me lembro de todas as humilhações que passei por estes covardes…

Todos precisam saber que existem irmãos dispostos pra matar e pra morrer em defesa dos mais fracos… Que ainda estão na condição de ser incapazes de se defender…

Everyone needs to know that there are brothers ready to kill and die in defence of those who are weaker … Who are still incapable of defending themselves …

‘Bullying’: the cause and effect

This debate had already started in 2003, when Edmar Aparecido Freitas, ex-pupil at the State School Colonel Benedito Ortiz, in Taiuva, a small town in the state of Sao Paulo, opened fire on his ex-classmates. He injured seven of them and then shot himself. It seems that ‘during his childhood and into adolescence [Edmar] was the target of sneering and bullying by his ex-classmates’. In one of his videos, Wellington paid homage to Edmar for this fact, and indicated that his ‘followers’ revered him, always remembering him in their prayers.

Anderson, one of Wellington’s ex-classmates, commented in Diálogos Políticos (Political Dialogues), saying:

Eu estudei com esse rapaz e ele tinha problemas psicológicos, ele sempre ficava sozinho e os demais alunos zombavam dele pelo motivo de sempre andar com a cabeça baixa.

Specialists’ opinions show that ‘even though he suffered from bullying (…) Wellington committed the killings because of his psychological problems’.

Cleodelice Fante, bullying researcher and currently doing a doctorate in Educational Sciences at the University of the Balearic Islands, Spain, has published an in-depth analysis of motivations and consequences as much as regards the bullies as the bullied:

Este fenômeno comportamental atinge a área mais preciosa, íntima e inviolável do ser, a sua alma. Envolve e vitimiza a criança, na tenra idade escolar, tornando-a refém de ansiedade e de emoções, que interferem negativamente nos seus processos de aprendizagem devido à excessiva mobilização de emoções de medo, de angústia e de raiva reprimida. A forte carga emocional traumática da experiência vivenciada, registrada em seus arquivos de memória, poderá aprisionar sua mente a construções inconscientes de cadeias de pensamentos desorganizados, que interferirão no desenvolvimento da sua autopercepção e auto-estima, comprometendo sua capacidade de auto-superação na vida.

The blogger Vinicius Fleury, in his blog Livro Mecânico (Mechanic Book), believes that the fact that Wellington had been a victim of ‘unusual problems’ at school, had ‘a tendency towards psychological problems’ and the fact of his ‘not having had any support’ are ‘explanations’ for the shooting, even though they do not justify it:

o bullying que ele sofreu naquele colégio teve uma grande parcela de culpa, assim como os envolvidos em causar o bullying. Todo mundo era moleque, ninguém sabia o que estava fazendo direito, mas isso não exclui um fato. Se aconteceu, não da pra voltar no tempo. Agora vai de cada um saber conviver com sua parcela de culpa, mesmo que ninguém tenha tido essa intenção.

Girls paying homage to the victims of the massacre at Tasso da Silveira School, in Realengo. Photo by Daniel Marenco on Flickr with Creative Commons License

For the blogger and educationalist Maria Frô, school has to be the most sacred place at any time, and concludes:

o mundo adulto é responsável pelas gerações futuras. Não fujamos de nossas obrigações. Isso significa que todo adulto deve ser responsável por qualquer criança. Isso significa, por exemplo, olharmos para além dos nossos umbigos, de nossas crias, de nossos alunos, isso exige de nós um compromisso maior e real com políticas públicas que sejam capazes de incluir, educar, prover de espaços culturais e de lazer, formar e amar todas as nossas crianças. Elas merecem um futuro melhor que balas na cabeça em seu espaço escolar.