Nohemí's cousin, Leonela, who was left without her playmate. Photo: Daniela Aguilar.

The original version of this article was written by Daniel Aguilar and published on Connectas in May 2014.

Ecuadorian children are leaving the country by the dozen, bound for the United States. They don't have visas, but they do have some light luggage. And there are people — traffickers in Ecuador, smugglers in Mexico — who charge for the journey: up to $20,000 for each traveler. The children's parents want them in the US and are willing to pay whatever it costs, even if their children have to endure the worst experience of their young lives to complete the trip. On some occasions, the children cannot reach their destinations and return; in other cases, they die on the way, without ever reuniting with their families.

In the United States, the thousands of unaccompanied children crossing the border (90,000 by the end of 2014, according to projections by the Department of Homeland Security) is now considered a humanitarian crisis. The phenomenon has motivated the US to hold intense meetings with the heads of state in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, where the vast majority of these children originate. The president of the UN General Assembly, Ban Ki-Moon, US President Barack Obama, and Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto addressed the issue in a meeting with the Vatican Secretary of State on Sunday, August 13. All of them assured the public that they are searching for a resolution to the situation.

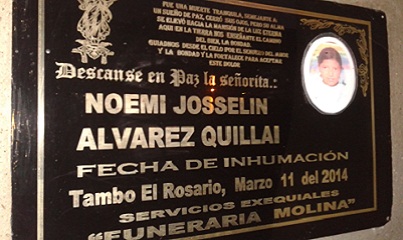

In Ecuador, however, no major authority figure has said so much as a word in public about the crisis. One exception has been the tragic death of Nohemí Álvarez Quillay, the 12-year-old girl who perished in a Mexican shelter after journeying unsuccessfully from Ciudad Juarez to the US border. In Quillay's case, Deputy Minister of Transportation María Landázuri launched an investigation, even going to Mexico to “demand” clarification about the girl's death on March 11. State officials have shared their condolences and publicly lamented this tragedy. Even President Rafael Correa, passing through New York City in April, went to hug the girl's parents, who are undocumented in the US and, like many others, risked their little one in the wolf's den.

Nothing is said about the rest of the children who leave the country, however, and there are more than just a few. The justice system does not investigate these cases, either, which Romeo Gárate, a prosecutor from Cañar, acknowledged, saying that Nohemí's death is “the only case” he can remember, when asked about child trafficking.

Honduras: a launch pad to the American dream

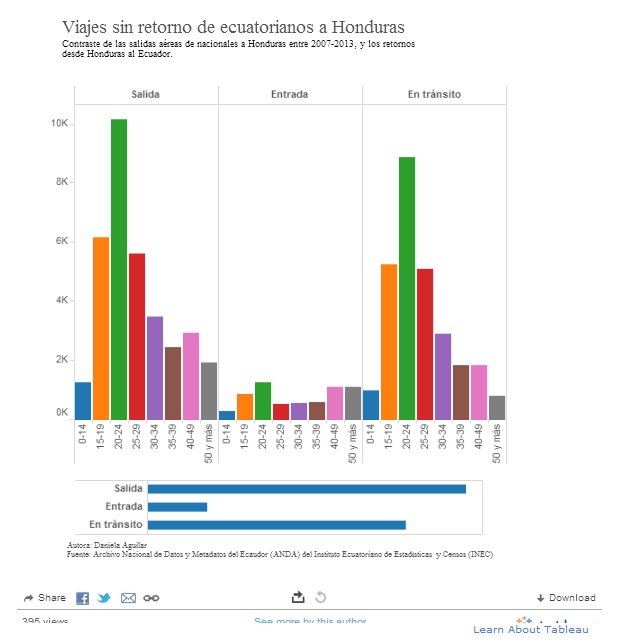

Since the need for a visa between Honduras and Ecuador was eliminated, one-way trips have soared. Between 2007 and 2013, 992 children were lost after leaving Ecuador for Honduras via plane. This figure by LA HISTORIA, incidentally, differs significantly from the migration statistics of international entries and exits in the National Data Archives (Anda). A total of 1,286 minors between 0 and 14 years of age traveled to Honduras during this period, but only 294 returned. This statistic increases with adolescents between the ages of 15 and 19, where 5,255 failed to return from their trips to Honduras.

One way trips for Ecuadorians to Honduras.

For every one child who leaves, 20 adults emigrate. During the same six-year period, 21,403 travelers over the age of 20 left and never returned. The government lifted visa requirements “primarily to promote bilateral tourism,” as reported by the Foreign Ministry at the time. Ecuadorians have embraced this language, too. Of the 27,650 citizens who never returned from Honduras between 2007 and 2013, 22,678 said they were going for tourism.

“Legislation must be created for this situation to prevent it from continuing, because it is nothing more than a field, the legal system, where we come in, and after it comes the State that must create a more direct policy to solve this”, said Romeo Gárate, an attorney from Cañar.

Gárate admits that the outflow of minors who leave to reunite with their parents has increased over the past three years. Honduras is just one of the many stops en route to America that employs trafficking networks to bring Ecuadorians to the border between Mexico and the US. Ecuadorians also cross into Colombia, like Nohemí Álvarez and two other boys, brothers from Cañar, aged 14 and 16, who were deported last week from Colombia as illegal immigrants.

The annual statistical reports from the country's National Institute of Migration (INM) also capture the number of Ecuadorians at the Mexican border. Between 2010 and 2013 alone, 2,663 Ecuadorians entered detention centers, after being detained. The number of detainees is rising sharply. 177 minors were recently returned to Ecuador. According to the latest report by the US Department of Health and Human Services and the EFE Agency, 96 percent of children succeeded in crossing the border last year, and 49,567 have already reached their families inside the United States.

Nohemí's tombstone in the cemetery in El Tambo, a province in Cañar (Ecuador). Photo: Daniela Aguilar.

Tambo, the tip of the iceberg

“First off, I must report that there are some students who normally attend classes but disappear at a certain point.” That is how Milton Correa, the principal at the El Tambo school, begins his talk at one of the only public schools in the Cañar region. This was the last institution that Nohemí Álvarez attended before starting her trip.

Surrounded by green hills, the El Tambo school welcomed last year 1,042 students between the ages of 12 and 17. During that time, teachers reported a surge in child labor migration and human trafficker activity.

For every unexplained absence, lead instructors investigated and reported their findings. “Without a doubt, I can say that 40 students have left this school during this school year. Some are gone, some have migrated, and others attempted to migrate,” says Nube Chogllo, a school counselor who collected the teachers’ reports. “We know that they left because of information that shared with us — by a relative, a friend, a colleague. They tell us: ‘s/he is in Nicaragua, in Guayaquil, in Mexico,’ but time goes by and some have crossed [the border] and others come back.”

There have been times when teachers learned that a child was about to migrate and they tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade them to finish the school year, at least. As Principal Correa explains, the main problem is that the children's parents organize the move to the US. “This phenomenon cannot be counteracted because those who are listening to us are more often the ones responsible for taking care of the children,” he says. “I don't know how to reach the people who migrated, to convince them not to put their children at risk,” Correa admits. He also argues that the direction of “family reunification” needs to be reversed, if parents are serious about their children's well being. If parents have already attained some economic stability in the US and want to be with their kids, they should come back, he says.

Of all the students at the El Tambo school who have fallen victim to trafficking, Nohemí Álvarez Quillay is the only one remembered for her tragic death. Though she never finished the school year before her first voyage north, Nohemí was automatically transferred to the eighth grade. When her first trip ended in failure and she returned to Ecuador, Nohemí attended only a month of classes before setting out on a new journey. Nube Chogllo interviewed the girl, before she left. At the time, Nohemí said only that she had tried to reached the US once, and wasn't sure if she would attempt it again. The counselor holds back tears when thinking about what the little girl had to live through: “Oh, if Nohemí could talk now, what would she tell us?” she mutters between long pauses. “These are mysteries we will never be able to solve.”

Leonela's loneliness

Leonela is 12 years old with straight hair and tanned skin. Her days are spent in school and wandering among the rice farm that separates her grandparents’ clay-brick house and the cement one built by her parents and uncles, all illegal immigrants in the US. She lives in El Rosario, an indigenous community in the district of El Tambo.

It has not been long since she was running alongside Wendy and Nohemí, her cousins who left Ecuador at the beginning of the year with coyoteros to be reunited with their parents in New York. She knows Wendy arrived and Nohemí died along the way, but she tries not to think about the circumstances. The fact is that Leonela was left without her playmates.

According to reports, many children are subjected to physical and sexual abuse in transit to the US. They are vulnerable to child prostitution gangs and kidnapping. Children always carry the telephone numbers of their relatives in their belts or shirt cuffs and are passed from one trafficker to another, usually at border crossings.

Ecuador's former penal code, which was reformed just last month, condemns both human traffickers and& “those responsible for the protection and custody of the children or adolescents, be they parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, siblings, or guardians or any other person, who facilitates the execution of this illegal activity.” In lieu of this legal protection, the Ecuadorian government has established nothing to stop parents living illegally in the United States from paying traffickers to bring their children to them. The new Integral Penal Code, approved by the National Assembly, specifically removed this paragraph in Section 11 of the law's Crimes Against Migration section.

Nohemí Álvarez was found hanging from a shower curtain in a Mexican hostel belonging to the National System for Integral Family Development. In Mexico, police detained and soon released the smuggler traveling with the girl. They've since reactivated an arrest warrant for the man. In Ecuador, the District Attorney's office initiated a preliminary investigation against four people, two of whom have already been arrested. Nohemí was sexually assaulted, according to a staff member from the Tambo District Attorney's office — an end very different from the inscription on her gravestone: “A peaceful death, like a dream of peace she closed her eyes, but her soul rose to the mansion of eternal light”.

1 comment