This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon.

Important issues for Peruvian communities, especially for Amazonian communities, have been temporally pushed into the background by the presidential elections. Nevertheless, the recent decision by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to ask the Brazilian government to immediately suspend the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam project [es] has brought similar projects, supported by Brazilian companies in Peru, under discussion once again.

In the case of Belo Monte (the third largest in the world), the IACHR stresses the importance of the rights of indigenous peoples to be consulted [es] in order to give their own free and informed consent [es], as serious social and environmental repercussions are expected.

In Peru, the biggest hydroelectric projects with the most publicity til now have been the Inambari and Pakitzapango plants. The latter is part of the Growth Acceleration Program (a plan that aims to improve the Brazilian economy) and also includes the Belo Monte and Madeira Projects in Brazil [es].

Those projects between Peru and Brazil are also included in the Energy Agreement signed last year in Manaus [es]. With this agreement, Peru would export 6,000 megawatts (MW) to the neighbor country [es]. In addition to this, six hydroelectric power plants are included in this project.

The six stations located at the borderline: Inambari (2,000 MW), Sumabeni (1,704 MW), Pakitzapango (2,000 MW), Urubamba (900 MW), Vizcatán (750 MW) and Chuquipampa (800 MW) are part of a project estimated in 16 billions US dollars.

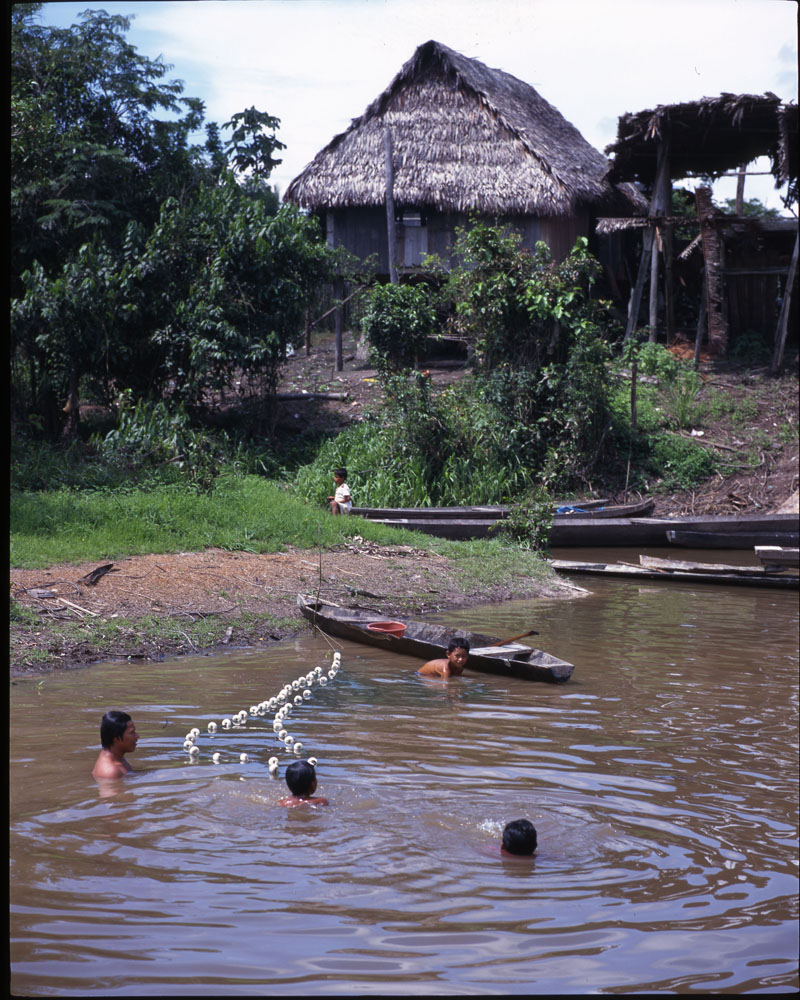

Rivers are a source of water, fishing, a means of transportation, and a vital source in the daily life of Amazonian communities. Natives of the Ucayali jungle, Peru (Photo: J. Enrique Molina)

In addition to that, although developers of Inambari [es] have tried to inform people [es] in social networks (they have created accounts on Twitter and Facebook) this information has not seemed to convince [es] the people of the regions that will be affected by those projects.

Neither does it seem to convince the Ashaninka people. As a matter of fact, they reject the Pakitzapango project in the Ene River [es] in the Junin region because they consider it a sacred place. According to their oral legends, this place is the ancient cradle of the Ashaninka people.

Ruth Buendia, a native leader, explains this situation in the Ideele Radio [es] blog:

La preocupación es que con las centrales hidroeléctrica Tambo 40 y Paquitzapango habrá una inundación de nuestras tierras, un desplazamiento forzoso de nuestros hermanos a pesar de que las comunidades nativas son tituladas, destrucción de bosque y la afectación económica de nuestros hermanos. Cerca de 10 mil ashánincas más colonos, o sea, estamos hablando de 12 mil personas aproximadamente. Con Paquitzapango y Tambo 40 se viene un terrorismo, ya no con armas pero sí económico…

Miguel Tejada provides a broader explanation regarding the effects of the social impacts of those energy projects in the blog GranComboClub [es]:

La construcción de las centrales van a tener impactos sociales importantes: decenas de miles de colonos y nativos desplazados. Quien conoce la selva sabe que todo el territorio amazónico ya tiene dueño, o tiene propietario o posesionario. ¿Los EIA [Estudios de Impacto Ambiental] van a contemplar todos los costos sociales que las centrales implican? ¿O va a pasar lo de siempre en nuestro país, que el costo social va a recaer sobre las poblaciones pobres, discriminadas y sin poder que se asientan sobre lo que serán los futuros lagos? Un analista ambiental conocido mío, cuya empresa fue contactada por los brasileños para hacer el EIA de Inambari, me contaba que su empresa hizo un análisis a partir de fotografías satelitales, y determinaron que sólo esa central implicaba el desplazamiento de más de diez mil personas, y que compensarlas adecuadamente implicaba un gasto de relocalización y de reconstrucción de toda la infraestructura actualmente existente (casas, carreteras, escuelas, centros médicos, chacras, etc.), que no bajaba de menos de un billon de dólares. ¿Cuánto afirman los brasileños que van a gastar en compensaciones sociales? A lo sumo, doscientos o trescientos millones de dólares.

Javier Albañil Ordinola, in Alto Piura blog [es], relates those issues to the elections by commenting on the declarations of presidential candidate Ollanta Humala. Some bloggers doubt [es] his unbiased opinion regarding this issue since his campaign consultants [es] also worked in the Brazilian campaign [es], in which Luis Inácio “Lula” Da Silva won the presidential elections.

En Inambari y Puno los pueblos se han movilizado contra este proyecto incluso hasta LIMA el 12 de octubre del 2010 CON LA PRESENCIA DE LA CONFEDERACION CAMPESINA DEL PERU Y DEL FRENTE UNICO NACIONAL DE LOS PUEBLOS DEL PERU con miles de campesinos PUNEÑOS. Ollanta declarò a LA REPÙBLICA [un diario local] que explicarà las bondades de este proyecto. COMO SI EL PUEBLO SE MOVILIZARA POR IGNORANCIA, desconociendo el derecho elemental de los pueblos a ser consultados. NO SON INDÌGENAS IGNORANTES COMO CREE OLLANTA.

Humala has declared to the press that if he took office as president, he would grant a popular consultation on those projects, but many people do not believe him.

The debate still unfolds on social networks. An example of this is Carlos Mauriola (@mauriola), who tweets:

Si Humala es el Lula peruano, me imagino qué será Inambari en su supuesto gobierno….

Following the same thought, Rafael Vereau (@Rafa_Vereau) asks:

Inambari: ¿Cómo resolvería Humala el proyecto al que se niegan los puneños pero que tiene comprometidos importantes capitales brasileros?

The developers of the Inambari Project have created a webpage in which they inform people about all facts related [es] to the project and answer some questions that they have received through email and social networks. This is one of their responses:

El proyecto Inambari es una concesión de 30 años y luego se entrega al Estado Peruano… Egasur está abocado al desarrollo de un proyecto como Inambari y espera que se pueda ejecutar siempre y cuando la población directamente involucrada lo decida. El proyecto se desarrollará en 5 años y se deberá cumplir con los acuerdos con la población antes del inicio de operaciones. El modelo considerado en Itaipú no es el mismo que el propuesto para Inambari… El tema de precios, distribución y porcentajes según los acuerdos que puedan existir son temas que escapan de la empresa ya que se discuten a otro nivel.

In the meantime, to have a broader picture of this issue, Peruvians are trying to learn about the experiences related to the construction and commissioning, the environmental [es] and social [es] impacts of similar projects [es] in the region, like Itaipu and Yacyreta, to have an idea of what they can expect [es] in Peru in the near future.

Itapú Binacional, considered the biggest in the Southern and Western hemispheres and the second biggest in the world. (Photo: J. Enrique Molina).

This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon.

2 comments