About 700 km away from Bangalore, across a couple of remote villages in the Bidar district, a quiet revolution has been going on. No, not a political one, but a remarkable pilot project in telemedicine.

Local pediatricians are using the iPhone to connect with experts in Bangalore for screening and diagnosis of a potentially blinding condition in newly born infants, ROP (retinopathy of prematurity), so they can be treated within 48 hours. Already 1600 infants have been screened and 160 have been treated successfully.

Cut across to North-East India's Tripura Vision Centre project which is effectively utilizing ICTs to reach rural masses with quality eye care services through tele-ophthalmology.

e-Health and more specifically telemedicine, promises to revolutionize rural health care in India soon. It is a welcome development, given the inadequacies of health care in rural areas.

The ambitious aim of India’s first National Health Policy [NHP], framed in 1983, was to achieve the goal of Health for All, by 2000 AD, through the provision of comprehensive primary health care services. Yet, given the country’s vast geographical spread, huge population, inadequate rural infrastructure and paucity of health care personnel, trying to make health care accessible to all has presented seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Consider these daunting statistics:

- Over 72% (that would be over 620 million) of India’s population lives in its 638,588 villages.

- Government spending on health care is a mere 0.9% of GDP (2006 data) while the WHO recommended figure is around 5%. Of this, very little reaches the rural millions.

- India has about 5.97 physicians and 7.9 nurses per 10,000 population while the global norm is 22.5. Of these, 75% of medical specialists live and work in urban areas. There is a huge shortfall of medical personnel in rural areas.

- The number of hospital beds in rural areas is only about 0.19 per 1000 patients (Urban India=2.2, World average = 3.96, and developed countries =7.2)

- 66% of rural Indians do not have access to critical medicine

In an article in PLos Medicine, Sanjit Bagchi, a medical practitioner and medical journalist based in Calcutta, India, writes:

The poor infrastructure of rural health centers makes it impossible to retain doctors in villages, who feel that they become professionally isolated and outdated if stationed in remote areas.

In addition, poor Indian villagers spend most of their out-of-pocket health expenses on travel to the specialty hospitals in the city and for staying in the city along with their escorts. A recent study conducted by the Indian Institute of Public Opinion found that 89% of rural Indian patients have to travel about 8 km to access basic medical treatment, and the rest have to travel even farther.

Keenly aware of the problem at hand, the GOI, in partnership with both public sector as well as private sector organizations, has been trying to promote and implement telemedicine and e-health projects across various states since 1999.

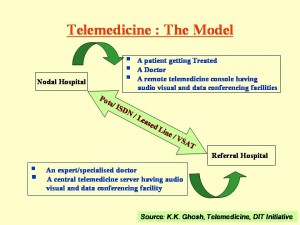

The basic telemedicine model as described by DIT's K.K.Ghosh in his presentation “Telemedicine: DIT intiative” [ppt] is as follows:

India saw telemedicine in action on a large-scale for the first time in 2001 after the earthquake in Gujarat, when the Ahmadabad-based Online Telemedicine Research Institute established a communication system from Bhuj, one of the worst hit places and hence pretty inaccessible. Soon they had a disaster management system up and running that allowed for the electronic transfer of medical needs, data etc., and enabled medical specialists to provide consultations from far away places through video-conferencing.

Other government and private players in the telemedicine space in India, especially in connection with the semi-urban, rural poor/ isolated communities and tribes can be found in this 2008 report from ehealth-connection.org. They include:

- Department of Information Technology (DIT) & Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC), which falls under the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. DIT has been carrying out telemedicine pilot projects across various states such as West Bengal, Tripura, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab.

- ISRO, offering connectivity backbone through satcom applications such as GRAMSAT

- The Ministry of Health & Family welfare and its National Rural Telemedicine Network working under the wings of the National Rural Health Mission

- Private hospitals such as Apollo (Ex: The Aragonda project)

Sanjit Bagchi points out:

The efficacy of telemedicine has already been shown through the network established by the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), which has connected 22 super-specialty hospitals with 78 rural and remote hospitals across the country through its geo-stationary satellites. This network has enabled thousands of patients in remote places such as Jammu and Kashmir, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Lakshadweep Islands, and tribal areas of the central and northeastern regions of India to gain access to consultations with experts in super-specialty medical institutions. ISRO has also provided connectivity for mobile telemedicine units in villages, particularly in the areas of community health and ophthalmology

In the following video, Mr. Chaturvedi, Director of The National Rural Health Mission in India, speaks about the ‘over-arching’ program, launched in 2005.

On why telemedicine is good for India, Dr. K. Ganapathy, President of the Apollo Telemedicine Networking Foundation had this to say:

The distribution of specialists in India is indeed lopsided. There are more neurologists and neurosurgeons in Chennai, than in all the states of North eastern India put together… The increasing availability of excellent telecommunications, infrastructure and video conferencing equipment will help provide a physician where there was none before.

(…)

This also ensures maximal utilisation of suburban hospitals. The general practitioner in the rural/suburban area often feels that he would loose his patient to the city consultant. With Telemedicine the community doctor continues to primarily treat the patient under a specialist’s umbrella. With modern software/ hardware at either end 90% of the normal interaction can be accomplished through Telemedicine.

The journey of telemedicine in India is however, not without challenges. Sanjit Bagchi writes:

“There are inevitable difficulties associated with the introduction of new systems and technologies,” according to Sathyamurthy (Programme Director, Telemedicine, ISRO). “There are some who needlessly fear that they will lose their jobs. Although the systems are user-friendly, there are others who are affected by the fear of the unknown in handling computers and other equipment. There is a feeling that the initial investment is high and hence financially not viable.” In addition, there may be technical hitches, such as low bandwidth and lack of interoperability standards for software.

Sanjay Prakash Sood of the Centre for Electronics Design & Technology of India mentions some other challenges on the road to e-health such as lack of health infrastructure and services, shortage of computer-savvy health care personnel, and poor quality of communication services in many of the cities.

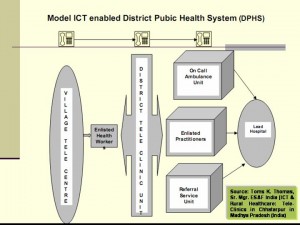

Toms K. Thomas, Senior Manager at ESAF India in his presentation“ICT & Rural Healthcare: Tele-Clinics in Chhatarpurin Madhya Pradesh (India)” points out that:

There is a need for public sector to be an enabler who invests in infrastructure –Living condition of the poor, Power, Road , Transport -ENABLING ICT TO OPERATE

He also talks about the basic infrastructure required for a model ICT enabled District Public Health System (DPHS)

The Indian government slogan “Health for all by 2000AD” may in the end have been an over-ambitious dream that has fallen by the wayside. It still remains to be seen, whether or not today's promise of health care delivery to India's rural millions via ICT will succeed in transforming tomorrow's reality.

2 comments

This sounds to be good.

After Google Bus project in Rural India, this is one fascinating thing I have heard of.