Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims. Central pillar contains names of the 168, 767 victims of the Nagasaki bombing who have died so far since the war. Photo by Nevin Thompson.

On August 9, Japan marked the seventieth anniversary of the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki. Although the 1945 destruction of Nagasaki has been traditionally observed each year, the 2015 commemoration was held as the remaining ageing hibakusha survivors who remember the day continue to die, and with them the memory of the horror of Japan's Pacific War.

The seventieth anniversary of the bombing of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki comes at a time of growing unease in Japan as the country's governing coalition is busy “reinterpreting” Japan's “Peace Constitution” to allow the country to legally go to war.

“Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays”

During the month of August, Japan remembers the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9, and the end of a long and ferociously bloody “Pacific War” on August 15.

Traditionally, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima has overshadowed the bombing of Nagasaki that occurred just a few days later.

Some of the reasons are logistical: compared to Hiroshima, which has its own stop on Japan's high-speed rail line, Nagasaki, located in the far west of Japan on the island of Kyushu, is isolated and hard to reach.

Nagasaki also has very few reminders of the bombing. While Hiroshima's distinctive Genbaku Dome has become both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a an iconic symbol of the horrors of nuclear war, Nagasaki has been rebuilt and most of the buildings and structures affected by the blast have vanished into history.

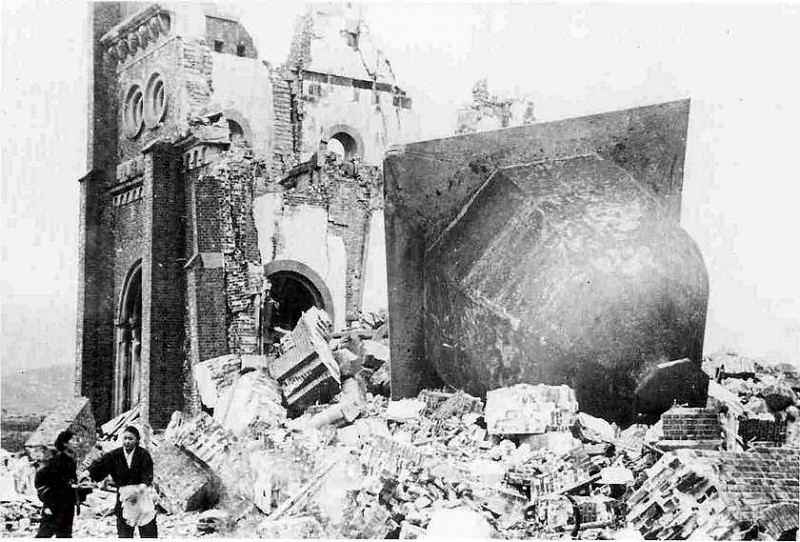

In Nagasaki, the bomb exploded directly above Urakami Cathedral, one of the largest Christian churches in Asia at the time. It represented Nagasaki's nearly 400-year connection to Christianity in 1945 (the original Urakami Cathedral itself dates back to 1895).

Urakami Tenshudo (Catholic Church) Jan.7, 1946. Photo by AIHARA,Hidetsugu. (1909-). Image is public domain.

Unlike the blasted remains of the Hiroshima Trade Hall (now known as the Genbaku Dome), which remain as they were on August 6, 1945, what little of Urakami Cathedral that survived the 1945 Nagasaki bombing was taken away.

All that remains of Urakami Cathedral are a few red brick columns, preserved at the hypocenter of the bomb.

Remains of Urakami Cathedral, Nagasaki (hypocenter of explosion). Photo by Nevin Thompson.

Writing in the Japan Times, Tomoko Otake notes that remembering the victims of the bombing of Nagasaki is complicated by the location of the hypocenter itself.

While the bomber crew was intent of targeting the rail depot and busy shipyards located in the heart of Nagasaki proper, they mistakenly bombed the suburb of Urakami to the north of the city.

In 1945 Urakami was not yet considered part of Nagasaki, and, Otake writes, was home to both the Kakure Kirisitan religious minority and Japan's “untouchable” dowa social caste.

For her Japan Times piece, Otake interviews Nagasaki historian Shigeyuki Anan (阿南重幸) of the Nagasaki Human Rights Center:

Anan, who has viewed the atomic bombing of Nagasaki as a lens through which to look at wider issues of human rights and discrimination against religious and ethnic minorities, says some Nagasaki residents — who were faithful to the local Suwa Shrine — took the bombing of Urakami as a sign that non-Shinto believers were “punished.”

“They said the bomb fell in Urakami, not Nagasaki,” Anan said.

Such a sentiment among locals polarized Nagasaki, keeping them from uniting in an appeal for peace, experts say.

Nagasaki Bomb Hypocenter in March, 2015 – Urakami, Nagasaki. Photo by Nevin Thompson.

Ask yourself “What can I do for the sake of peace?”

As in Hiroshima, the Nagasaki's memorial ceremony each year is led by the mayor of the city. Several thousand people gather in a large “peace park” located on a hill overlooking the epicenter of the bombing in the suburb of Urakami, to the north of Nagasaki's downtown core.

This is the first time I have attended [the Nagasaki memorial service]

Hibakusha survivors are asked to speak, and politicians, including the Prime Minister of Japan, lay wreathes and make their own remarks on the bombing. The ceremony is typically broadcast live on television.

Nagasaki memorial service, August 9th, 2015

Just over 34,000 hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) remain in Nagasaki. On the seventieth anniversary of the bombing, their average age has topped 80 years old for the first time.

As people who actually experienced and suffered the aftermath of the horror of the bombings continue to die, there are worries that few people in Japan will remember the true, horrible nature of warfare in the nuclear age.

As part of his speech at the ceremony on Sunday, August 9, Nagasaki Mayor Tomihisa Taue directly addressed the need to remember the past, and for future generations to not forget to work for peace:

To the young generation, I ask that you do not push wartime experiences aside saying that they are stories of the past. Understand that the wartime generation tell you their stories because what they speak of could, in the future, happen to you as well. Therefore, please inherit their wish for peace. Please imagine what you would do in such circumstances, and ask yourself “What can I do for the sake of peace?” You, the young generation, have the power to transcend national borders and create new relationships.

Is Japan Really Committed to Abolishing Nuclear Weapons?

A few days before the Nagasaki memorial ceremony on August 9, 2015, Prime Minister Shinzo raised eyebrows when he neglected to mention or make reference to Japan's “3 non-nuclear principles” (非核三原則 Hikaku San Gensoku) during his address at the Hiroshima memorial ceremony.

As Prime Minister Abe and his government have worked hard to set up a legal framework that will permit Japan to go war, discarding seventy years of post-war pacifism, there are also worries that Japan is in fact a covert nuclear-threshold state.

Abe's failure to recognize Japan's 3 non-nuclear principles during his Hiroshima address, critics say, is yet another example of his government's “incremental” approach to changing Japanese society, in this case carefully preparing the way for Japan to emerge as a nuclear state.

As if in response to these fears, Abe dutifully reiterated Japan's commitment to the country's 3 non-nuclear principles when he addressed attendees at the Nagasaki ceremony on August 9th.

Remembering the Dead in August

平和への願いを灯籠に=浦上川で万灯流し-長崎 http://t.co/WIDdz9qLPz pic.twitter.com/G2yDhFirdK

— Cubeニュース (@cube_news_site) August 9, 2015

Lanterns are released on the Urakami River with a prayer for peace.

Ceremonies commemorating the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the end of the war itself coincide with Japan's traditional O-Bon festival.

Observed in mid-August each year, O-Bon marks the time when ancestors return to visit the family home. At the end of the festival, many families send off their visiting ancestors aboard floating paper lanterns released onto a river or into the ocean.

In Hiroshima and Nagasaki this practice has special poignancy as the lanterns are accompanied with prayers for peace and a hope that no one else will ever experience the horrors of nuclear war.

1 comment