This is the third in a series of interviews with Iranian journalists and writers who have dedicated their careers to communicating Iran's complexities and contradictions to those outside of the country. Read the first with Golnaz Esfandiari, and the second with Kelly Golnoush Niknejad.

It was Sunday 12 July, 2015, the night before what was supposed to be the last deadline for the Vienna talks. Nina Ansary and I had been trying, in vain, to schedule a phone call over a few different time zones for at least a month. We finally reached each other on the eve of the day Iran's future was supposedly being negotiated by a team of diplomats in Vienna.

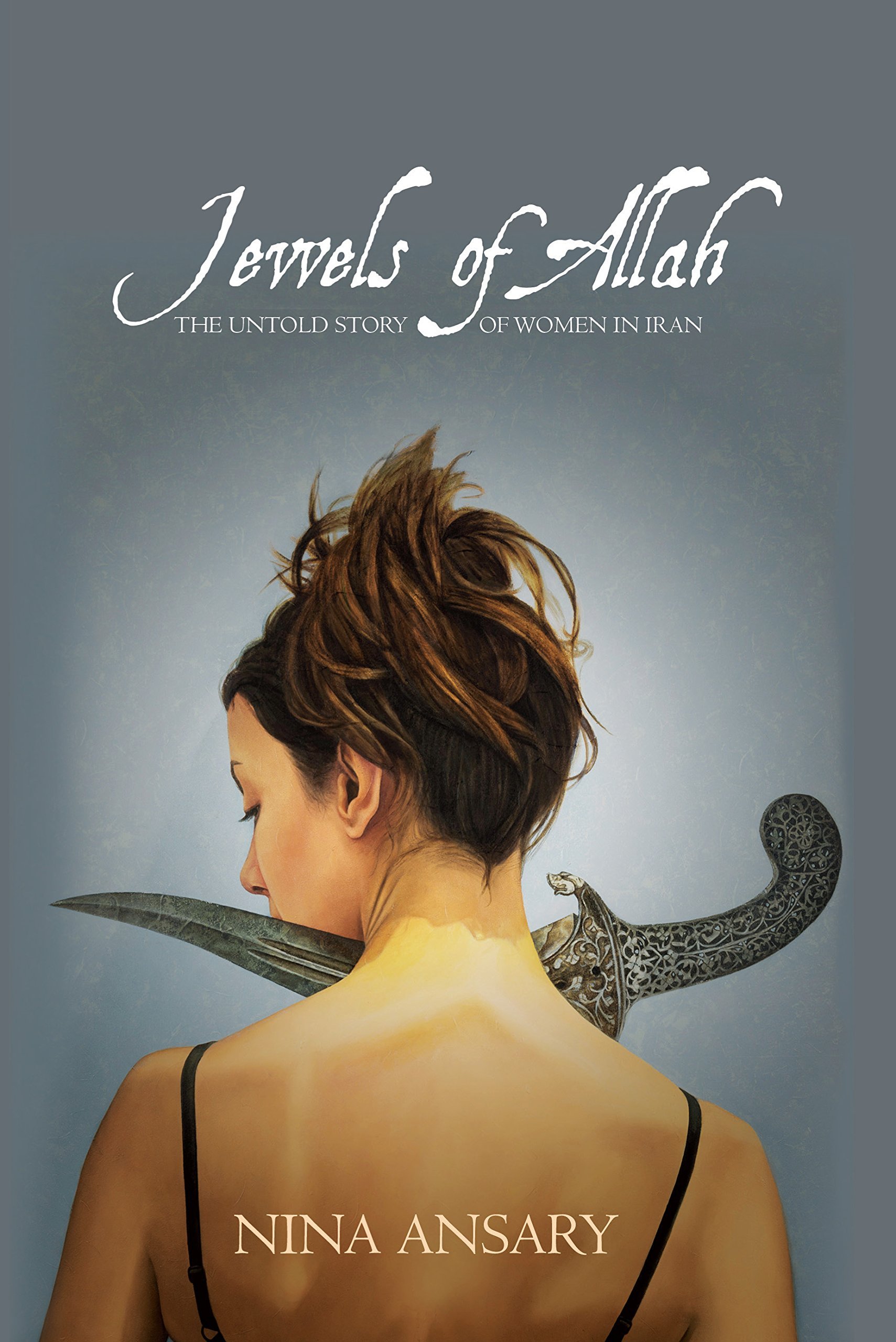

Studies that make worthy contributions to the field of gender in Iran are few—notable exceptions are Janet Afary’s Sexual Politics in Modern Iran and Haideh Moghissi's many articles and books that look at feminism's role in revolutionary Iran. But while Ansary's efforts are not a first, Jewels of Allah: The Untold Story of Women in Iran is the first book to cover the leading feminist political movements from the end of the 19th century to the present. The book is filled with case studies and descriptions of movements such as the evolution of women's education throughout the Pahlavi and Islamic era, as well as feminist reformist journalism in the late 90's. Janet Afary's sociological readings and Moghissi's populist revolutionary studies have compiled the history of women, but using a different methodology. Ansary's book is a solid introduction for any lay reader looking for a overview of feminism in modern Iran.

What is innovative about the book is the way Ansary magnifies certain historical moments. She dedicates one whole chapter to Shahla Sherkat, the activist-editor who has struggled to keep Zanan, Iran's longest running feminist publication, afloat throughout the forced closures and stealthy political maneuverings of the reformist era into the present moderate administration. By providing a window into the work of these contemporary Iranian women, Ansary shows that feminism comes in all shapes and sizes. That it comes, for instance, in the guise of the only female firefighter in a far-flung Iranian city, or—as in the Sherkat case study—in the form of a journalist defying social taboos in order to share the work of the global feminist movement.

“Every woman has the right to define the feminist mantra according to her own vision,” Ansary told me during our conversation. “She has to define feminism to her own cultural context.”

Indeed, the purpose of Ansary's book is to allow us to understand how women have shaped Iran’s recent history, and continue to do so, while working to establish their rights and equality in a society that has traditionally marginalized them.

Ansary herself comes from a background invested in Iran's political climate. She left Iran with her family during the revolution, when she was 12 years old. Her father had been part of the deposed Shah’s government. This came as a surprise to me, as Jewels of Allah is devoid of the usual ideological traps that tend to ensnare those who study Iran. Ansary doesn’t support or identify with the regime that has held power since the Islamic Revolution: “On a very emotional level I feel a deep connection to my homeland,” she told me, “but for the last four decades. . . . this regime is a dark stain and a dark cloud over the real Iran.” At no point in the book, however, were the Pahlavi era's contributions to feminism valorized. In fact, Ansary's book embraces the Islamic-inspired feminism that arose post-1979.

“What transpired today for women in Iran owes itself to many different pockets of history. These were different pockets of opportunities where women were afforded a voice,” explained Ansary.

Why do I connect Ansary’s book with the recent nuclear negotiations? The topic came up, naturally, as we chatted on the evening before the deadline.

“I look at it from a strictly humanitarian perspective,” says Ansary. “These negotiations are not addressing women’s rights violation, and other human rights concerns. However, sanctions have debilitated the general population at large, and I’m hoping if one door opens, other doors will also open. . . it will make the regime feel they are accountable to the world, beyond just the nuclear concerns. But taking the current regime out of the equation, I welcome the change for the Iranian people.”

And her thoughts on the future of Iran, and the place of women in it?

“Cautiously optimistic. . . only because I see their resilience. And this is because female activism has yielded partial results: women were not allowed to serve as judges, but can now serve as investigative judges. Women weren’t allowed to enter certain fields of study, and over the years they have been able to penetrate into male dominated areas such as medicine and engineering. I'm cautiously optimistic, but I believe women will be at the forefront of any change in Iran.”