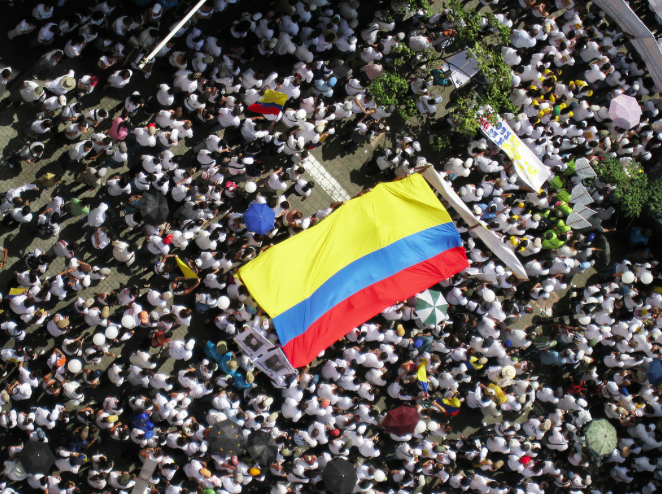

Image of the 2006 Colombia soy yo [I am Colombia] march in Medellín. Flickr photo by xmascarol under Creative Commons license.

One concrete example of how people have begun to put the violence in context are initiatives by both the government and local communities to preserve collective memory: to remember those who are missing, to restore the names and the dignity of those who have died, and to promote the message that the horror should never be repeated. Although there are many programs, Global Voices is focussing today on four in particular.

1. National Centre for Historical Memory (CNMH): On its official website, the CNMH, which is a government initiative, is defined as:

Establecimiento público del orden nacional, adscrito al DEPARTAMENTO PARA LA PROSPERIDAD SOCIAL (DPS), que tendrá como objeto reunir y recuperar todo el material documental, testimonios orales y por cualquier otro medio relativos a las violaciones de que trata el artículo 147 de la Ley de Víctimas y restitución de Tierras. La información recogida será puesta a disposición de los interesados, de los investigadores y de los ciudadanos en general, mediante actividades museísticas, pedagógicas y cuantas sean necesarias para proporcionar y enriquecer el conocimiento de la historia política y social de Colombia.

A national public institution, affiliated with the DEPARTMENT FOR SOCIAL PROSPERITY (DPS), the objective of which is to recover and collect all the documentary material, oral testimony, and any other information about violations according to Article 147 of Colombia's Victims and Land Restitution Act. The compiled information will be available to interested parties, investigators, and the general public through museum and educational activities as well as other means by which awareness of Colombia's political and social history can be enriched and disseminated.

The centre also underscores the importance of using Twitter to preserve collective memory, creating a special account with the following mandate:

Investigamos, con autonomía y énfasis en la voz de las víctimas, la evolución del conflicto armado en Colombia para que no haya olvido ni repetición.

We are investigating, independently and with particular attention to the victims’ voices, how the armed conflict in Colombia evolved so it will never again be repeated.

2. “Remembering is a pleasure.” That is the name of an initiative led by the community of Valle del Guamuez in the southwestern Department of Putumayo. It is word play on the name of the local rural police station, Inspección de El Placer, which was the focal point of kidnapping and repression beginning in the late 1990s. This initiative's goal is to “showcase the region's rich cultural heritage“ and bring attention to peaceful alternatives in an area once beset by violence.

Haven of Peace Community Centre, Pueblo Bello, Antioquia. The building was designed in collaboration with the local community. Photo used with permission.

3. Salón del Nunca Más: This is a shared meeting space that declares “never again.” It is where people in the community can leave messages for missing and lost loved ones using logbooks and other media. The website reminds us:

“Los lugares de memoria son también lugares de consciencia. Quien visita un lugar de memoria, no puede irse igual, debe irse con interrogantes” Maritze Trigos

A place of memory is also a place of awareness. Whoever visits one cannot leave without being affected, without questioning.” Maritze Trigos

In the northern Colombian town of Granada, Antioquia, there is local construction underway that's aimed at recognizing the past:

” un proceso de construcción permanente de memoria. Estos son los pedazos de ladrillo que trajimos para la construcción de esta nuestra memoria. Este barro doloroso será transformado, y seremos fortalecidos en la unidad de nuestros sueños”.

“Building memory is an ongoing process. These are the shards of brick that we have brought to build our memory. This evocative clay will be transformed, and we will be strengthened by our collective dream.”

Paulina Villa Posada writes that the meeting room that says “never again” to war is transforming ideas of forgiveness into action.

Las fotos de los muertos y desaparecidos de #granada Antioquia el Salon del nunca mas es un ejercicio… https://t.co/cg1Cih4odq

— Paulina Villa Posada (@PaulinaVillaP) May 2, 2015

The pictures of #granada‘s dead and missing in the Salon del nunca mas is an exercise….

The Salón del Nunca Más can be seen on YouTube, in a video where community members discuss the logbook project to remember their loved ones:

4. Remanso de paz [haven of peace] Social and Community Centre: Built in the village of Pueblo Bello in the Department of Antioquia, once part of territories largely controlled by the paramilitary commander Carlos Castaño, the centre was unveiled in December 2014. Today it hosts a permanent round-table where members of the municipality come to create colourful patchwork quilts incorporating the names of victims of violence, as well as a tree of life, illustrating their hopes and dreams for change. Through its own memory meeting place, Pueblo Bello is highlighting important events in its history, such as the disappearance of 43 farm workers, who were arbitrarily removed from their houses without any kind of mediation after the community was accused of allowing cattle to be stolen from the paramilitary commander. The order was given to “take the men in exchange for the animals.”

Regional TV station Teleantioquia broadcast the following report about massacres that left a ghost town in their wake:

Meanwhile, the newspaper Ciudad Sur published the story of one of the women of Pueblo Bello who recounts the terrible events she and fellow residents experienced.

La mirada fija en los retratos de quienes ya no caminan las calles de Pueblo Bello, refleja el dolor que se niega a abandonar la memoria de Enaida Gutiérrez. Esta mujer de 50 años fue testigo de las cuatro masacres que las Farc y los paramilitares ejecutaron en este pequeño poblado del municipio de Turbo, en el Urabá antioqueño.

Eneida Gutiérrez stares at the photos of those who can no longer walk the streets of Pueblo Bello, her fixed gaze reflecting the pain she can never forget. This 50-year-old woman witnessed the four massacres that the FARC and their paramilitary opponents inflicted on this hamlet in Turbo, in the Uraba district of Antioquia.

As forward-looking as these measures may be, they also attest to the challenges Colombia faces both in the peace process and in terms of the repercussions it will have throughout the country. From major urban areas to mountain villages, there are many conversations to be had by all citizens about negotiating a roadmap to reconciliation.