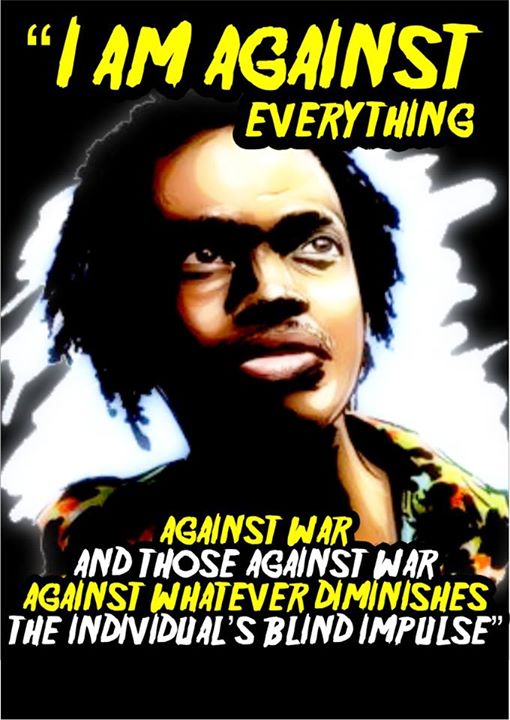

Dambudzo Marechera's image and his poem THE BAR-STOOL EDIBLE WORM. Image posted on his Facebook page.

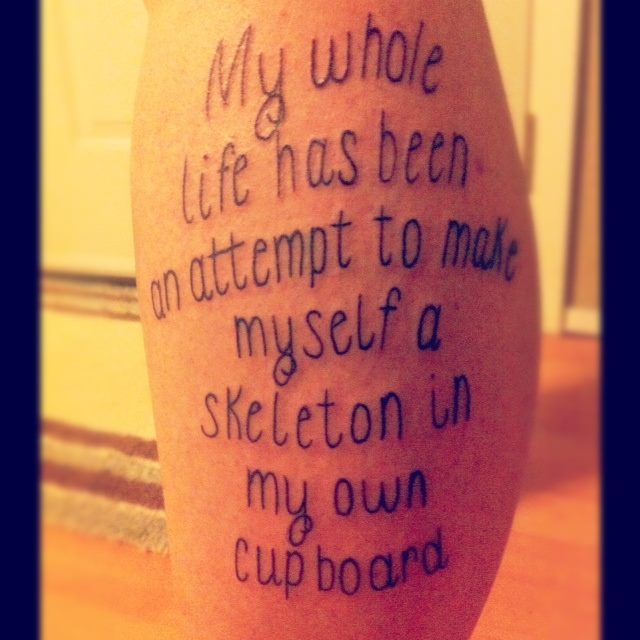

Dambudzo Marechera‘s Facebook page celebrates the life and times of one of the most eccentric figures in African literature. Marechera was a Zimbabwean writer and poet who died at the age of 35 in 1987 after leading a life that he described as “an attempt to make myself a skeleton in my own cupboard.”

Marechera, whose form of writing has been described by his official biographer as “literary shock treatment,” attended St. Augustine's Secondary School in Zimbabwe, the University of Zimbabwe, and New College, in Oxford. He was expelled from all three.

When he was chased from New College, he wrote the following to his ex-girlfriend:

I think by now you have heard what happened when those hypocrites in administration chased me from their white university giving me an option between being sectioned or expelled. I chose the latter, a decision which shocked them out of their warped wits.

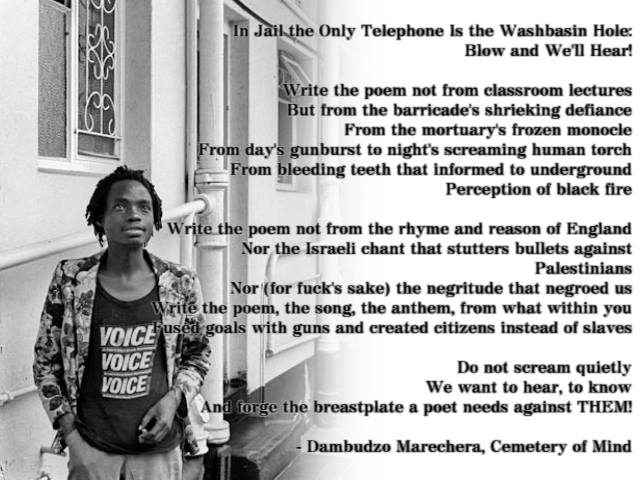

Marechera wrote House of Hunger, Black Sunlight, The Black Insider, Mindblast, and Cemetery of the Mind. The first text won the Guardian First Book Award in 1979.

Celebrated African writer Helon Habila describes the opening line of House of Hunger as the coolest opening line in African fiction:

I got my things and left.

This, the opening line to Dambudzo Marechera’s The House of Hunger, apart from being the coolest opening line in African fiction, is a fair summary of the writer’s life. He was always getting his things and leaving; not that he had many things to get—in his last years, homeless and reduced to sleeping on park benches in Harare, Zimbabwe, all he had were his typewriter and a few books.

On the Facebook page, the administrator and his fans share memorable lines from Marechera's books and interviews, discussing the complexity of his thoughts and writing style.

On the subject of God and Creation, Marechera said:

There's an artist who specialises in portraits. Know what he did to portray the character of his clients? He studies their boots. If he was here right now he'd study your boots to find out everything about you. Like the others study palms, and the others study the shape of your skull. Phrenologists. Others read the tea leaves at the bottom of your cup. And there all those others who study your dreams and the consistency of your shit and the mucus running down your nose and the map of pimples on your face and backside. Life. Like we are all hidden from God and he has to study us like that to discover the nature of the bastards he created. If you create life out of yourself, is that incest? That's what he did, rubbing himself up to ejaculate us into the world.

“I am against everything,” Marechera declared in The Bar-Stool Edible Worm, one of his most popular poems:

I’m against everything

Against war and those against

War. Against whatever diminishes

Th’ individual’s blind impulse.

Marechera didn't hold out much hope for anarchism:

“While I was writing Black Sunlight I was reading books on intellectual anarchism to reinforce my own sense of protest against everything; I was reading Bakunin and Kropotkin. Intellectual anarchism is full of contradictions in the sense that it can never achieve its goals. If it achieves any goal at all, then it is no longer anarchism.

Dambudzo's words tattoed on a fan in the US. Photo by Lori Ambo. Used with permission.

Marechera's version of children literature:

Blah is being dragged kicking and screaming to school, to church, to the dining table, to the nation's flag, to bed without supper. Blah is how big human beings torture little human beings. If you are a little human being you must report them to the United Nations which has fists bigger than your father's. […]

Television really tortures little humans. It makes them think of BMX bicycles and goodies. It makes them little prototypes of the blah adults they will grow into with time. It makes them enjoy watching (on TV) the destruction of things so that they are too tired to destroy the society that is actually a lunatic asylum. A lunatic is someone who knows there is something wrong somewhere but does not know exactly what. An asylum is where they are going to put me when they catch you reading all this I am writing.

On being tired of saying “black is beautiful”:

“No, I don’t hate being black. I’m just tired of saying it’s beautiful.” The House of Hunger

“I closed the huge doors behind me and walked softly towards the altar. I was in the opium of the people. The huge cross dangled from chains fixed to the roof. I stood looking at the crucified Christ. He looked like He needed a stiff drink. He looked as if He had just had a woman from behind. He looked like He had not been to the toilet for two thousand years. He looked like I felt. That was the connection.” Black Sunlight

On September 24, 2014, the administrator of the page asked fans to share their favourite quotes from Marechera:

Bekezela Nyoni chose one about black writers and language:

For a black writer the language is very racist; you have to have harrowing fights and hair-rising panga duals with the language before you can make it do all that you want it to do. It is so for feminists. English is very male. Hence feminist writers also adopt the same tactics. This may mean discarding grammar, throwing syntax out, subverting images from within, beating the drum and cymbals of rhythm, developing torture chambers of irony and sarcasm, gas ovens of limitless black resonance.

Moses Mosaic Tshumah Matibhe selected a remark about Marechera not being an African writer:

“If you are a writer for a specific race or a specific nation,then f**k you.”

Marechera questioned anyone who called him an African writer, arguing that literature should not be pigeonholed by race or language or nation.

3 comments

Dear Author, I love Dambudzo’s work!!!!!!! but he surely didn’t have a facebook page.

Mjabuli,

The Facebook page was opened by his fans not himself. Thanks.