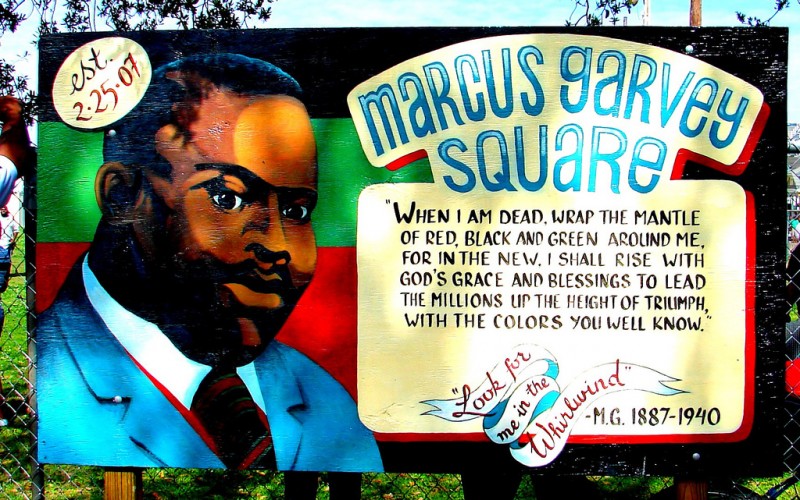

This past weekend marked the 127th anniversary of Marcus Garvey [2]‘s birthday. One of the Pan-Africanism [3] movement's staunchest supporters, Garvey is celebrated as the first National Hero of Jamaica.

Two Jamaican bloggers, one from the diaspora and one who lives on-island, chose to commemorate the day by focusing on different aspects of his life. Litblogger Geoffrey Philp says that the example of Garvey's life and work helped him to understand a critical question for people of African descent: What does it mean to be a man? Philp explained [4]:

After travelling through the Americas and into the center of colonial power in the West Indies, Garvey realized that […] in order to survive the brutalities of slavery [Africans] had been reduced to a childish state in which they had relinquished personal and collective power. Cowed into submission, Africans at home and abroad lived in fear of outside forces over which they had no control, and even after gaining ‘freedom,’ their existence was based on the level of servility to their former masters.

As Garvey saw it, Africans […] could either live in a reactionary state in which they only responded to crises […] or take control of their lives by assuming personal and collective responsibility.

This philosophy of personal and collective responsibility, organised around the principles like self-respect, purpose, community and education, was key to Garvey’s ideas about manhood and nationhood — and it struck Philp that nearly 75 years after his death, and in the context of the shooting [5] in Ferguson, Missouri, “and other daily insults to Africans at home and abroad, either we can continue living in a childish, reactionary state where we do not assume responsibility for our lives or we can organize and plan accordingly. The choice, as it was then and now, is ours.”

In contrast, Carolyn Cooper, who blogs at Jamaica Woman Tongue, examined Garvey's love life [6], saying that Amy Jacques, his second wife, offered “an intriguing account of Marcus Garvey’s first marriage to Amy Ashwood in her book Garvey and Garveyism.” From all accounts, the first Mrs. Garvey was quite demanding and Garvey soon discovered that he could not balance his first love, the advancement of Africans, with her needs — so they divorced and he remarried. Jacques, his second wife, devoted herself to not only Garvey, but also to his work; many of his books and papers would probably not have been published without her help, but she paid for the efforts with ill health. Cooper surmised:

Having sacrificed her health for Garvey’s cause, she fleetingly rebels against the callous regime of domestic servitude she had willingly embraced.

Perhaps, Amy Jacques should have followed Amy Ashwood’s example and made a lucky escape. But who would have ensured the completion of The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey and so consolidated the great man’s reputation?

The moral of this love story is quite complicated: Great men often need self-sacrificing wives.