Three countries in francophone Africa are fighting to exit prolonged social crises that stem from broken political systems. Over the past five years, the Central African Republic, Madagascar and Mali went through political takeovers that involved the participation of armed factions:

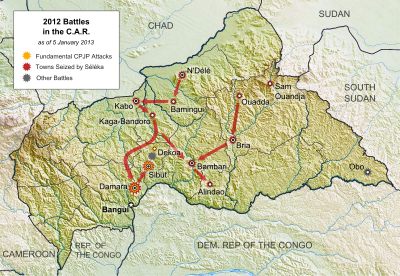

- In the Central African Republic, the Seleka rebels took over in March 2013 and Michel Djotodia was named president. The country is currently going through severe civilian conflicts that forced international military forces to intervene.

- In Madagascar, army forces removed then president-elect Marc Ravalomanana and installed in his place the current leader of the transition Andry Rajoelina. The run-off for the presidential elections was held on December 20. The official final results are expected on January 18.

- In Mali, while facing the threat of their country being split in two by armed rebellion in the north, a group of soldiers led by then-Captain Sanogo removed the elected President Amadou Toumani Touré and installed a transition government in his place.

All three nations face similar long odds before a sustainable political system can be stabilized. Here are three conditions that civil societies in these respective countries have identified in order to start the reconstruction of the political system.

Madagascar

Emmanuel Jovelin, a lecturer at the Université of Lille, and Lala Rarivomanantsoa, a professor at the University of Antananarivo, wrote a book called “Opinion publique et bonne gouvernance à Madagascar” [Public opinion and good governance in Madagascar]. The authors addressed a multitude of issues pertaining to Malagasy citizens’ perception of their political representatives. One of their most outstanding chapters is the proposed framework for evaluating governance in Madagascar. They opine [fr]:

Le gouverné n'est pas, comme on a toujours tendance à le croire, une masse informe que le gouvernant pourrait modeler à sa guise. L'opinion qu'il se fait de la gouvernance prend des formes variées parfois contradictoires pour mettre en place une administration efficace. […] Mais l'ensemble des opinions recensées dans cette étude peut constituer la base d'une gouvernance respectant les règles de la démocratie […] La succession des différents régimes depuis l'Indépendance peut s'expliquer par une faiblesse des structures intermédiaires de dialogue (à travers l'administration et au sein de la société civile) qui n'ont pas fonctionné comme on aurait pu le souhaiter.

Citizens are not, as one tends to believe, a shapeless mass that could be shaped as rulers would wish. Citizens’ opinion of governance takes various forms sometimes contradictory to the establishment of an effective administration. […] Still, all opinions identified in this study can form the basis of a governance that respects the rules of democracy […] The succession of different regimes since independence can be explained by a weakly structures intermediate dialogue (through government and within civil society) that did not work as one might wish.

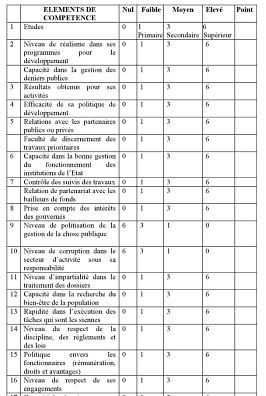

Below is the matrix they propose to evaluate the performance of the governing administration:

Screenshot of the framework to evaluate governance in Madagascar from an extract of the book by Jovelin, Rarivomanantsoa – CC-license-BY

The first two lines details the skills/competence that any governing bodies should showcase and provide a scoring chart :

1. Scoring for “Academic Achievement” : primary school: 1; secondary school: 2 ; higher education: 3.

2. Scoring for the feasability of development programmes : weak : 1; medium: 2; strong: 3.

Central African Republic

The conflict in the Central African Republic has escalated to an alarming level of victims: the death toll has now reached at least 500, according to the local Red Cross.

The following video illustrates the level of fear and insecurity across the country:

The OCBG blog based in Bangui reports on the proceedings meeting on good governance [fr] in the CAR:

En Centrafrique ou ailleurs, par crainte ou par méfiance et quelquefois désintérêt à la chose politique, nombreux sont ceux qui se cachent [..] Notre pays a été marqué par des mutineries successives, des coups d’état et des rebellions ce qui affecte sa stabilité et son développement économique [..] En effet, les centrafricains attendent des gouvernants de demain : L’organisation d’une véritable armée nationale ; la garantie sécuritaire des populations sur toute l’étendue du pays ; l création des infrastructures (écoles, routes, hôpitaux, bâtiments administratifs etc.,) les accords de Libreville ne peuvent résoudre les problématiques récurrentes à notre pays, dans la mesure où Libreville a été qu’une course à l’échalote et des maroquins, aucun des protagonistes n’a posé la question relative à l’urgence sociale qui prévaut

In CAR and the greater region, many people are hiding because of fear, distrust and disinterest towards politics […] Our country has been marked by successive mutinies, coups and rebellions which affects its stability and economic development […] In fact, the CAR expect the following from their leaders: the establishment of a truly national army, the guaranteed safety of populations throughout the country, the creation of infrastructure (schools, roads, hospitals, administrative buildings etc.). The Libreville agreement cannot solve the recurrent problems of our country because the Libreville agreement [a ceasefire agreement signed in January 2013 that stipulated the integration of the opposition in the government] was a race for money and power, neither side even addressed the question of social emergency that prevails.

Mali

The Malian crisis was partly resolved by the French military intervention in 2013, but despite the presence of the peace forces, unrest is still prominent in the northern territory.

In light of many still unresolved issue of governance, Michael Bratton, Massa Coulibaly and Fabiana Machado report on the survey they conducted with Malian citizens on what they expect in a good governance [PDF] :

Malians prefer democracy to other political regimes but their perception of democracy is culturally distinct. Malian satisfaction with democracy is often seen in terms of the personal performance of individual political leaders. They judge the legitimacy of the state based on popular trust in public institutions and perceptions that public officials are not corrupt [..] Malians continue to regard the State as the most reliable provider of employment. They prefer cosnensus and unity to political and economic competition.

3 comments

Voices are made to be heard especially 2014 @ thanks to you’re blog I think you are making it possible for peoples voices to be heard great job. I also think the music still is the strongest voice of them all and has the strongest influence, and very universal. So T.Lee @ DesFly Wishes you & You’re Family A”Happy New Years,#Support #Closure The Hottest #Rapper In #NewOrleans #Real #Life #Music Cln http://t.co/aN5pLNFNxi Dty http://t.co/XeLuxoRtzD Thanks For You’re Time.