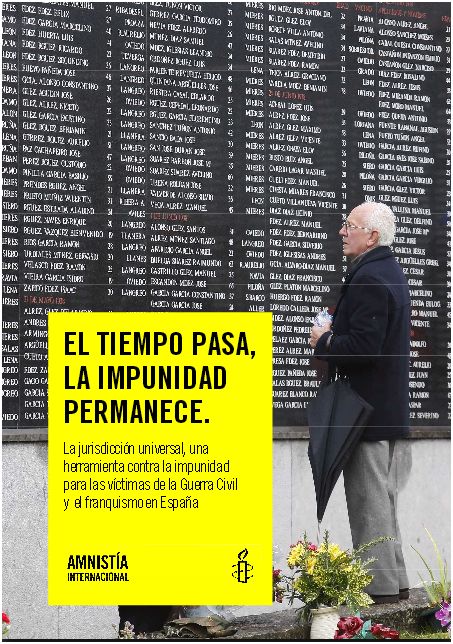

Time passes, impunity remains, the new Amnesty International (AI) report [es] published on June 17, 2013, analyses the investigation of crimes committed during Spain's Civil War and the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

AI accuses the Spanish government of protecting the impunity of the crimes committed during this period. The report's introduction makes the following hardline statement:

En este informe, Amnistía Internacional constata que el comportamiento del estado español parece estar orientado a buscar que se garantice la impunidad de los crímenes de la Guerra Civil y el franquismo. Así se deduce del rechazo de los jueces españoles, amparados por el Tribunal Supremo, de investigar, y la falta de colaboración del Gobierno y de la Fiscalía con la justicia argentina (como se explicará), para que otros países puedan investigar estos crímenes.

In this report, Amnesty International asserts the behaviour of the Spanish government is aimed at ensuring impunity for the war crimes that took place during the Civil War and under Franco. It's the only deduction we can surmise as to why judges -most notably those on the Supreme Court- have refused to investigate cases and the general lack of collaboration from both the Government and the Attorney General with the Argentine judiciary (explanation to follow), so other countries might investigate these crimes.

The report accuses the government of hindering and even preventing proper investigations of the crimes committed during the Franco era. The Spanish newspaper Público [es] detailled five ways in which the government is obstructing investigations:

1. El gobierno de España se entromete y no colabora

2. La justicia no investiga

3. La fiscalía facilita afirmaciones falsas

4. España no ha firmado aún su adhesión a la Convención sobre imprescriptibilidad

5. Se mantiene vigente la Ley de Amnistía de 1977

1. The Spanish government obstructs and refuses to cooperate

2. Courts refuse to investigate

3. The Attorney General enables false testimonies

4. Spain still hasn't become a signatory of the Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity

5. The 1977 Amnesty Law has not been repealed.

Ignacio Jotvis, author of the report, asserted during the presentation of his report that Spain's Judiciary has systematically impeded investigations of these crimes being conducted in Argentina, specifically citing how the Ministry of Foreign Affairs prevented Argentine judge María Servini [es] from taking victims’ official statements via videoconference.

Director of Amnesty International Spain Esteban Beltrán said, “Spain is making a vain attempt to turn the page having not even read it.” El Boletín [es] published further details shared during the report's presentation:

(…) la organización detalla que, de los 47 casos de víctimas del franquismo derivados de la Audiencia Nacional a los juzgados territoriales, se habían archivado al menos 38.

Amnesty International has found that at least 38 of the 47 cases of violations under Franco's rule referred from the National High Court to regional courts have been closed.

Though long past, the violations committed during the Civil War remain a very sensitive topic within Spain. The numbers of those that actually lived the war -which took place from 1936 to 1939- are now few, but there is no lack of Spaniards who grew up with a keen awareness of a family member's suffering as a result of absuses from one side or the other. It is then no surprise that the subject continues to be a controversial and divisive one, commonly resulting in a nasty debate whenever it appears in a newspaper.

One of the most routinely cited criticisms of these investigations is their limited representation only includes Republican victims. On a Huffington Post article [es], reader Elpaisdelamagia commented:

Crímenes hicieron los dos bandos, ahora solo se habla del franquismo. Lo peor de un país una guerra civil, la lucha de hermanos contra hermanos…

Los dos cometieron crímenes e injusticias, cuando se llegó a la democracia, lo que se intentó es llegar a la reconciliación, no se puede vivir con odio y resentimientos (…).

Crimes were committed by both sides, even though now we only talk about those done by the Nationalists and Franco. The worst thing for a country is a civil war, brothers fighting against brothers…

Both are guilty of crimes and injustices. When democracy came, it did its best to bring reconciliation with it. We cannot live with this kind of hate and resentment (…).

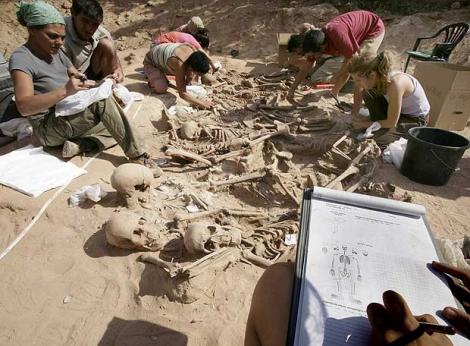

Some take issue with the country extending necessary resources searching for mass graves and classifying human remains during such an economic crisis as the current one. They contend it is futile to investigate crimes that took place more than 70 years ago when it is not even possible to prosecute the culprits because they have already died. Reader Mike Hammer commented on the Público site:

Mas que impunidad, los presuntos responsables ya han entrado en la eternidad. Los argentinos que parecen estar dispuestos a meter las narices en el tema deberían recordar lo inútil que resulta “gastar pólvora en chimangos…”

More than impunity, those allegedly responsible have already passed. The Argentines that are so willing to stick their noses in the middle of all this should remember how futile it is to “beat a dead horse…”

But there is a strong community backing the families of victims, who maintain their right to know what happened to their families, recover their remains and give them proper burials. On the blog Cosas de Antonio we read:

No se ha de pretender más que dejar las cosas en su sitio, que la historia diga la verdad de los hechos y que los muertos de las cunetas y de las fosas comunes sean enterrados y honrados como se merecen, (…) por darles el mismo trato que se les ha dado a los otros contendientes y por merecerlo desde el punto de vista humano (…).

We should try to set the record straight, make history tell the truth about what happened, and provide the dead in ditches and in mass graves the burial they deserve, (…) give them the same that has been given to other fighters, it's the least they deserve from a humanistic point of view (…).

Mercedes Pinto[es] left the following comment on the blog:

Yo creo que posicionarse en uno u otro bando para rescatar la memoria histórica también es un error. La guerra siempre la gana un bando, pero la perpetran dos. Hubo muertos en los dos lados (una de mis tías abuelas fue quemada en un convento, su padre murió en Paracuellos y el hermano de su madre a manos del ejército de Franco. ¿No es una locura?) (…)

I think to firmly position yourself on one side or another of history is a mistake. One side always wins the war, but two perpetrate it. There were deaths on both sides (one of my great aunts was burned in a convent, her father died in Paracuellos and her uncle at the hands of Franco's regime. Isn't that insane?) (…)

Journalist Olga Rodríguez (@olgarodriguezfr) tweeted this on the subject:

@olgarodriguezfr: A quienes se niegan a condenar el franquismo: Las heridas solo cicatrizan cuando se las trata. Por eso la impunidad marca tanto este país…

@olgarodriguezfr [es]: To those who want to refute the condemnation of the Franco regime: Wounds only heal when treated. This is why impunity is marking this country so deeply…

“We compensate for historical memories with an Alzheimer judiciary.” Cartoon by El Roto published on the website Federación Estatal de Foros por la Memoria.

On 26 May the Platform for a Truth Commission, comprised of more than 40 different groups and high-profile supporters, convened in order to “construct a memory of the victims that coincides with the official memory by the State and close, once and for all, open wounds.” According to the website periodismohumano [es]:

La Plataforma [por la Comisión de la Verdad] piensa llevar el asunto ante las instituciones internacionales como el Tribunal de Derechos Humanos y Estrasburgo. También al Parlamento Europeo pero con la finalidad de que lo que se apruebe en Europa, tenga legalidad en España

The Platform [for a Truth Commission] wants to bring the matter to international institutions like the Court of Human Rights and Strausborg. And to the European Parliament because in the end what is passed in Europe has legal implications in Spain.