In our attempt to discover the route of Brazilian Critical Masses, we spoke with two organizers of the Salvador Critical Mass [pt] (also known as “Bicicletada”), Roque Júnior and Rosa Ribeiro. Below, you find the second part of the interview, in which we get to know a little more about the city’s policies of urban mobility.

GV: How does the dialogue between the business lobby and citizen lobby – which is also called activism – take place in regards to urban mobility?

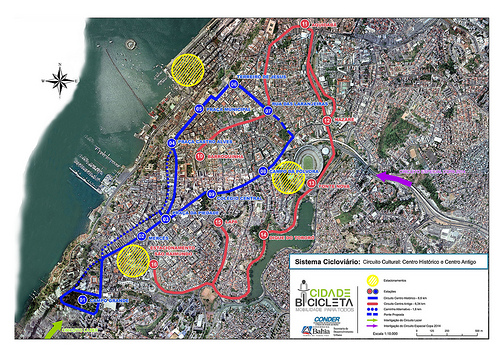

RR: In the municipality of Salvador, we do find some councilors/representatives with sympathy towards the cause and we’ve succeeded to have approved, one or two years ago, the law of bicycle mobility in Salvador. However, even though there is some sort of sympathy towards the idea, things rarely go beyond a piece of paper [pt]. (…) At the executive level, there was the “Cidade Bicicleta” (Bicycle City program) [pt], which developed (and even produced a detailed study) of a system of cycling mobility for the city of Salvador.

Cidade Bicicleta – Mobility for Everyone. Image by SecultBA, Secretariat of Culture of the state of Bahia, on Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

[The study] abandons the idea that bicycles are meant for leisure, and that bike lanes should be strictly located along the seashore, and moves ahead – at least in the project – to articulate connections among neighborhoods, from the suburbs to the downtown area. One can only consider bicycles as a means of transportation if one can actually see a system which coherently offers this kind of movement. If nowhere is connected to no place, of course nobody will use it. (…) That’s up to the State Government. The question is, however, that the State can only intervene with the Township’s backing. Although they have a very interesting project, I didn’t see any interest by Jacques Wagner [Governor of the state of Bahia] to implement it, plus there is no written agreement between the Township and the State Government on this.

When the international press arrives to cover the FIFA World Cup, it will say that Salvador has a bike lane. What you have at stake, and it also mobilizes the State sometimes, is the visibility: the construction of a city image, which is fake most of the times. (…) One of the main concerns during 2011 municipal elections in Brazil was the question of overcrowded towns, traffic jams, low quality of urban life, so the issue of urban mobility is fundamental these days. But, at the same time, we see the Federal Government giving full support for the production and sale of cars, all over the country. For example, over the past 10 years of the Lula administration and the current Dilma administration, we have witnessed the number of cars double in the city of Salvador.

Publicity video launched by the State Government of Bahia in 2010

GV: To what extent do cars remain a symbol of status and social upward mobility? How can public space be shared?

RR: Seven years ago, I didn’t have much hope that a transformation of spaces and that of the urban area could occur, due to society’s general lack of political interest. Why? Because that would require a restricted use of cars. This kind of transformation in Brazil doesn’t just lie on the space and physical order – instead it involves a social reorder, the social restructure.

“Respect one less car” – The “pedalada” event in São Paulo, 2010. Photo by Thiago Miranda dos Santos Moreira on Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Three years ago, when the middle class began riding bicycles, these probable car owners who are actually choosing bikes as means of transport, I thought to myself: “could things change?”. There is a very strong discourse in favor of bikes. The bike used to be linked to the stigmatized class of the low income population, and now we see a new discourse being born, placing bikes on top of cars as an object of social status. The bicycle is thus associated with a more interesting contemporary lifestyle, together with sustainability and a way of rethinking the city and its social relations, which is so recent I can’t describe… But here’s a reminder. It’s not about possessing, and what a person has. It’s about someone who needs this vehicle to move through town. It’s about the need. The use we make of cars as means of mass transportation in Brazil is absolutely insane.

About the political will to create some kind of transformation, it’s worth mentioning (…) that bikers of São Paulo made all election candidates ride bikes, and succeeded in getting them to sign a letter committing to this model of bikes as means of transportation. I think that São Paulo and Curitiba are cities with social movements that are making a difference today in that regard. (…) And there is a very favorable conjuncture in Brazil’s most mediatized city, Rio de Janeiro, in regards to the interest for bicycles because of urban construction to host the 2014 World Cup games and the 2016 Olympics. Today Rio de Janeiro has the largest cycling infrastructure in Brazil.

GV: In general, many people say they don’t use bicycles as a means of transportation due to lack of safety, violence (robberies) or traffic accidents. How can that be changed?

RJ: The first thing is to make a distinction between perceived insecurity and real insecurity. It seems to me there is a generalized perception of insecurity which contaminates the public. The public space we live in is hierarchical, and, within street hierarchy, the car comes first, pedestrian come last, and the bicycle is sort of in the middle, closest to the pedestrian. One can realize that people feel this disrespect. They will experience this disrespect, or they will visualize it and disrespect, you see? So I believe this turns into a generalized perception, as you can see these situations and you can say “I don’t want to experience, imagine or go through that”. Another thing is generalized fear, which is independent from traffic and present in public spaces. Being in public spaces brings up a series of possibilities outside the realm of security. So there is a fear of conflict in traffic, and fear of robberies.

GV: Do you see a way to reverse this? Any alternatives?

RR: I don’t know about reversion, but I believe that it makes a difference to have an urban infrastructure dedicated to bicycle riders, that actually provides security to them, coherently designed so they can cycle all over town. Many people say “oh, there’s no need for that, only education is necessary, learning to share”. But infrastructure attracts people who would never have the required courage, malice, attention and presence of spirit to face urban traffic. Others say that bike lanes are not meant for those who already ride bikes. They’re not for the sportsperson either. They’re meant for grannies, for children, for a larger public who could be moving around but do not believe in their physical potential to perform such movement. As soon as they start doing it though, they realize it’s very easy. People are stronger than they think.