This post is part of our International Relations & Security [1] coverage.

The hot pot of Chinese politics is still boiling madly after the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party and the leadership transition that took place in Beijing on November 14, 2012. Many see the composition of the new Politburo Standing Committee [3] as a defeat for outgoing President Hu Jintao, who failed to see his reformist allies promoted. Moreover, Hu stepped down as the chairman of the Central Military Commission sooner than expected. Were Chinese conservatives stronger than expected or did something weaken the reformists?

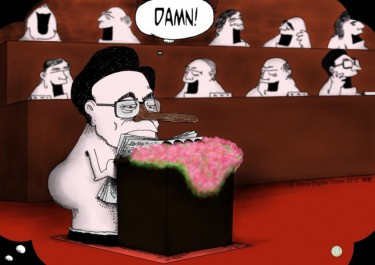

Just two weeks before the Congress started the New York Times published a story [4] alleging that members of Wen Jiabao’s family have amassed a combined fortune of $2.7 billion by using the Premier’s influence and close links between politics and business in China.

With Chinese politics already at boiling point, the New York Times article exploded on Sina Weibo [5], the social media site that is purported to be a reasonable reflection of public opinion. Comments expressing both surprise and disappointment flooded the Internet, but also many of unconditional support for Wen, reported Rachel Lu on Tea Leaf Nation [6].

With China’s censorship machine ready to stop [7] any “harmony disruption”, both the English and Chinese versions of the New York Times website were blocked [8]within hours of the article’s publication. However, Chinese netizens know creative ways to jump the Great Firewall [9] and had already been using the code word “Sparta” [10] (which has a similar pronunciation to ‘18th Congress’ in Chinese) in order to access the article. Lily Kuo explores on Quartz [11]how Chinese netizens got around the censors to read the article and discuss the issue. Kuo writes:

Chinese bloggers have been using various homonyms for the New York Times to get by the censors. One that translates to “twisted waist times” (扭腰时报) and sounds like the Chinese name for the paper has already been blocked. But “Cattle Times,” another homonym, seems to have gotten through for now.

Some have logically related the news story and its timing to what may be the greatest political scandal in the last months: the fall of high-flying politician Bo Xilai [12]. Despite the Party’s efforts to present it as an example of the fight against corruption, many perceived it as a clear sign of internal struggle. Bo Xilai is seen as a representative of the leftist wing of the party (which means conservative in China) that is pitted against reformists represented by Wen Jiabao.

In her post on Tea Leaf Nation [6], Lu collects some of the comments pointing in that direction:

“What position is the New York Times taking? Have they been bought out by the supporters of Mao?” asked one user. “All sides are making their final moves and positioning their pieces–that is what I think about the NYT’s headline today,” commented another. Some believe the newspaper is being used as a pawn in the power struggle, “This time NYT really does not understand China–too much of a puppet.” Another user wrote: “The information is probably given to the New York Times by left-wing powers in China, and the right-wing deserves it.”

Others still admire Wen for being the most senior and the most vocal among those Chinese officials who dare to openly call for reforms. “It doesn’t matter if these disclosures are true, I don’t expect high officials in the CCP [the Chinese Communist Party] to be clean anyway. I just hope that the liberals and the reformers can start real political reforms,” wrote one user.

Though it seems clear [13] that New York Times journalist David Barboza did much research in complicated corporate records, the possibility that someone may have helped him cannot be ruled out. This would not devalue his work, but it could help explain the dominance of the conservative wing once led by Bo Xilai on the new cycle of Chinese politics that now begins.

[14]This post and its translations to Spanish, Arabic and French were commissioned by the International Security Network (ISN) as part of a partnership to seek out citizen voices on international relations and security issues worldwide. This post was first published on the ISN blog [14], see similar stories here [15].

[14]This post and its translations to Spanish, Arabic and French were commissioned by the International Security Network (ISN) as part of a partnership to seek out citizen voices on international relations and security issues worldwide. This post was first published on the ISN blog [14], see similar stories here [15].