This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon [1].

Real estate speculation is taking over Brazil as the country experiences a boosting economy and a new round of consumption extravaganza: people are having access to more credit and are willing to pursue dreams like getting rid of rent and buying their own home. In this scenario, constructors, their suppliers and other companies involved in the real estate chain are taking over every free square meter in the cities and converting them into apartment buildings, commercial buildings and condos – all quickly built with the aid of new technologies in construction and easily sold thanks to the easiness of credit access. Such a phenomena poses some threats to nature and to society itself, as it changes the way people nest.

In Brasilia [3], the capital of Brazil, this theme is gaining momentum as property projects multiply, invading the last remains of the typical savannah vegetation, known as cerrado [4].

Brasilia is a modern city, a product of the creative minds of Lúcio Costa [5] (the urbanist responsible for the Pilot Plan project) and Oscar Niemeyer [6] (the architect responsible for the city´s architectonic projects). In the Pilot Plan, the superblocks (blocks 300m long) hold buildings no more than 6 floors tall so that everyone can admire the sky and, where possible, see the lake Paranoá [7]; the ground floor (pilotis [8] [pt]) is considered public space – it does not belong to the private space of the buildings – and is supposed to be shared by the community (based on the idea that people should circulate freely and that the buildings should float above everything [9] [pt], according to blogger Daniel Duende, “not occupying the spaces but rather placing themselves harmonically above them”). All these were part of an urbanistic trend in the 1960´s. For Fernando Serapião [10], an architect and an urbanist, the peculiar traits of Brasilia will find no parallel:

Apesar das virtudes, nenhuma outra cidade terá uma área residencial como a da capital brasileira. Suas contradições e problemas foram fundamentais para a evolução do pensamento urbanístico. Desde os anos de 1960, os urbanistas não rezam mais a cartilha que gerou Brasilia.

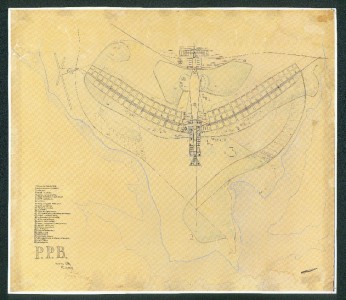

[11]

[11]Original image of the Pilot Plan, Brasilia, available from the Ministry of Culture of Brazil under a CC license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Brazil.

For Roberto Segre [12], who is also an architect as well as a critic and historian of Latin America architecture,

(…) a cidade expressa agora as contradições políticas, econômicas, sociais e culturais existentes no país.

The contradictions Segre mentions have hurt the utopia concepts of the capital of Brazil. Professor Carpintero [13] (p. 4-5) citing [pt] Brasilia's conceptual standards as proposed by Lúcio Costa [5], the urbanist responsible for Brasilia's Pilot Plan [14], summarizes the global idea of what a city means (or could mean):

Ela (a cidade) deve ser concebida não como simples organismo capaz de preencher satisfatoriamente e sem esforço as funções vitais próprias de uma cidade moderna qualquer, não apenas como URBS, mas como CIVITAS, possuidora dos atributos inerentes a uma capital … a cidade não é apenas construção – urbs -, mas lugar de cidadãos, – civis, civitas.

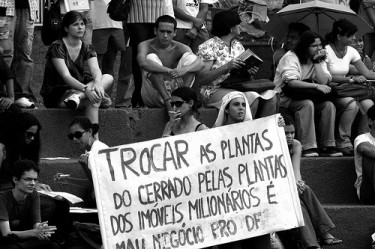

[15]

[15]"To trade savannah's plants for millionaire property plans is bad a bargain for Brasilia (Federal District)". Photo by Daiane Souza, used with permission.

The free areas left by Lúcio Costa, the bucolic scale [16], are now threatened by corporate plans that are taking advantage of Brasilia ever growing real estate market. Bloggers like Pedro Júnior [17] [pt] believe there's a property bubble [18] in Brasilia. With property offer rising, greater are the environmental costs. Construction sites are multiplying and this is happening against strong criticism: activists have denounced in a series of videos (watch video: 1 [19], 2 [20], 3 [21]) the impact (on nature and on the lives of an indigenous community located in the green area) of building Setor Noroeste (Sector Northeast), advertised as the first ecovillage [22] [pt] of Brazil.

During the process of public hearings that discussed the Noroeste project, even the indigenous presence in the lands of Setor Noroeste – in the place called Terra Indígena Santuário dos Pajés [23] [pt] or Reserva Indígena do Bananal [24] [pt] – has been questioned or treated with contempt. The former governor of the Federal District (where Brasilia is located), stated [25] [pt] (1min37sec) in a public hearing in 2007: “in that area (…) where Setor Noroeste will be built (…), there are exactly six indians living in that area”.

[26]

[26]Indigenous protest against the construction of Setor Noroeste. Photo from Movimento Cerrado Vivo, available in the blog Os Verdes de Tapes.

In order to build Sector Northeast, an area covered by cerrado [4] is already being deforested. Soon, in another expansion planned for Brasilia, the Setor Sudoeste (Southwest Sector) might host 22 new buildings with 6 floors each, in spite of community protests [27] [pt] and legal concerns [28] [pt] regarding the project, which was the result of an exchange between the Brazilian Navy, owner of the public land where the Southwest expansion might take place, and a construction company, which has offered to the Navy, in turn, a certain share of apartments in Águas Claras (a district 20 minutes far from Brasilia).

[29]

[29]Protest against real estate speculation in Setor Sudoeste and for the savannah (Cerrado). Photo from blog Grupo Currupião, 2009.

The speculation context contrasts with the fact that Brasilia was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site [30] in 1987. Cidadania Online [31] remarks [pt] that

O tombamento assegurou que as premissas urbanísticas do Plano Piloto não podem ser desfiguradas, nem pela especulação imobiliária.

On September 11th, Brazil commemorated Cerrado's day [32]. Some environmentalists and activists claim there's not to much to celebrate, though. The tropical savannah is also the stage upon which farmers are boosting agriculture. Cerrado, though rich in its biodiversity, is not as famous as the rain forest. The efforts to protect it are more diffuse, or, somewhat less coordinated in global terms. The statement on a recent report on The Economist [33] accounting that Brazil “is often accused of leveling the rainforest to create its farms, but hardly any of this new land lies in Amazonia; most is cerrado”, probably could be expressed by the average Brazilian who doesn't know that particular environment or who is not directly affected by its deforestation. It might be the case in Brasilia, where people and the government might not value the local vegetation.

In fact, SOS Parque Ecológico do Guará regrets [27] [pt] the lack of interest of the government of Brasilia for the environment and for quality of life.

Brasilia is not the only region where real state speculation is taking a stand. Dimas Santos, deputy mayor of the municipality of João Alfredo in the state of Pernambuco, on his blog says [34] [pt] that people consider him to be “against progress” when he reflects on the negative impacts of real estate speculation on nature. He also questions the role of speculators in Brazilian society and discusses the use of public funds to build the basic infrastructure in certain regions that, later on, have those benefits privatized by speculators who bought the land to do exactly that: wait for improvements and sell. From Dimas point of view, the current situation is summed up in a song by Chico Science, a local composer, who says that

a cidade não pára, a cidade só cresce: o de cima sobe, o de baixo desce.

To the global audience I ask if real estate speculation is taking place in your regions, too. Use the comments to answer, if you feel like sharing your stories.

This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon [1].